When the Duke of Edinburgh’s death was announced this morning, I found myself recalling a wonderful afternoon in Paris in 1992 when I had to show him around an exhibition. I was working for the Henry Moore Foundation at the time, and we were staging a huge show of his largest sculptures in the Jardins de Bagatelle in Paris. It had been the most complex logistical project I had ever worked on and the installation alone had taken three weeks. The lorries bringing the sculptures from Perry Green in Hertfordshire to Paris had to travel through the night as convoi exceptionel were not permitted on the periphérique later than 5am.

We would all gather at the magnificent baroque entrance gates to the Parc at around 6am, where the crane and lorry drivers would be standing around eating croissants and drinking coffee with the prostitutes who occupied that spot during the night hours. They were a fabulous group of people and we had many laughs about the ridiculous idea of lifting three or four tons of bronze over a set of Baroque gates every morning.

(C) M. Muller

The installation of 29 massive works by Moore was an interesting combination of heavy lifting and exact precision. Each work had to be lowered by crane or forklift onto a pedestal that was less than 5cm larger than the base of the sculpture. And it had to be done exactly right each time as any shifting around damaged the plasterwork on the breeze blocks which meant retouching and repainting.

By the time we had finished the exhibition in late May I had cycled hundreds of kilometres around the beautiful Jardins de Bagatelle, avoiding the peacocks. The opening of the exhibition was to coincide with a royal visit to Paris and would be conducted by Her Majesty The Queen with the Duke of Edinburgh, in the presence of the François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac, who at the time was Mayor of Paris. The Foundation’s director, the late Sir Alan Bowness, was to show The Queen around the exhibition and I was asked to guide the Duke.

I was given a few instructions about protocol including a warning not to ask any questions and not to leave long silences. When the Royal party arrived, I was standing in the appointed place and curtsied to The Queen, who looked at me with her piercing eyes, and then presented to the Duke with whom I set off, a few steps behind The Queen and Alan. We got to the first sculpture, Hill Arches. The Duke turned to me and said: ‘I don’t like Moore’s sculptures’. Oops. This was going to be a very long hour and a half, I thought. Then I remembered he was interested in engineering. ‘Well Sir’ I said, ‘shall I tell you how we got them into the grounds?’ He was fascinated and asked many questions about the cranes we used, the lorries making their stately progress across northern France and the prostitutes who shared our croissants with us.

At one stage we had to walk through a long lane between dense shrubs with no sculptures to look at but with a lovely view of the west of Paris in the distance. ‘I grew up over there.’ He said, pointing to Neuilly. He spoke a little about what it had been like growing up outside Paris and how he had known the Jardins de Bagatelle when he was young. Then there was silence. I got a bit anxious, so I decided to chance it and bring up my grandfather, who he had known well in the 1970s when he, the Duke, was Patron of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and my grandfather was the president.

At the mention of his name the Duke stopped dead in the middle of the lane, looked me straight in the eyes and said: ‘Good gracious, are you Phil Toosey’s granddaughter?’ When I said I was he went into a long speech about how much good work my grandfather had done for the Far Eastern Prisoners of War and what a great contribution the School had made to FEPOW health under his presidency. He ended by asking me: ‘Is your mother here today?’ When I said she was he insisted I point her out so he could go over and shake her hand, but not before he had met the lorry drivers who had brought the sculptures to Paris. As we approached the end of the walk, where the crowd of guests had gathered to meet the Royal party, he marched past all the dignitaries from the British Embassy and the Mayor’s office, straight up to Eric, the head lorry driver, whose 42nd birthday it was, and wished him a very happy birthday. ‘A date you share with me,’ he added with a twinkly smile. Of course, it was 10 June 1992, the Duke’s 71st birthday. Eric was overwhelmed but the Duke’s greeting put him at his ease.

He then walked over to my mother, who was shaking like a leaf, and said: ‘Hello Gillian, it’s very lovely to see you here.’ He talked briefly about her father and how much he used to enjoy seeing him in Liverpool when he attended meetings at the School of Tropical Medicine. After that, the Royal party left and Mum and I went out with my husband Chris and various other members of the Henry Moore Foundation team for a long dinner.

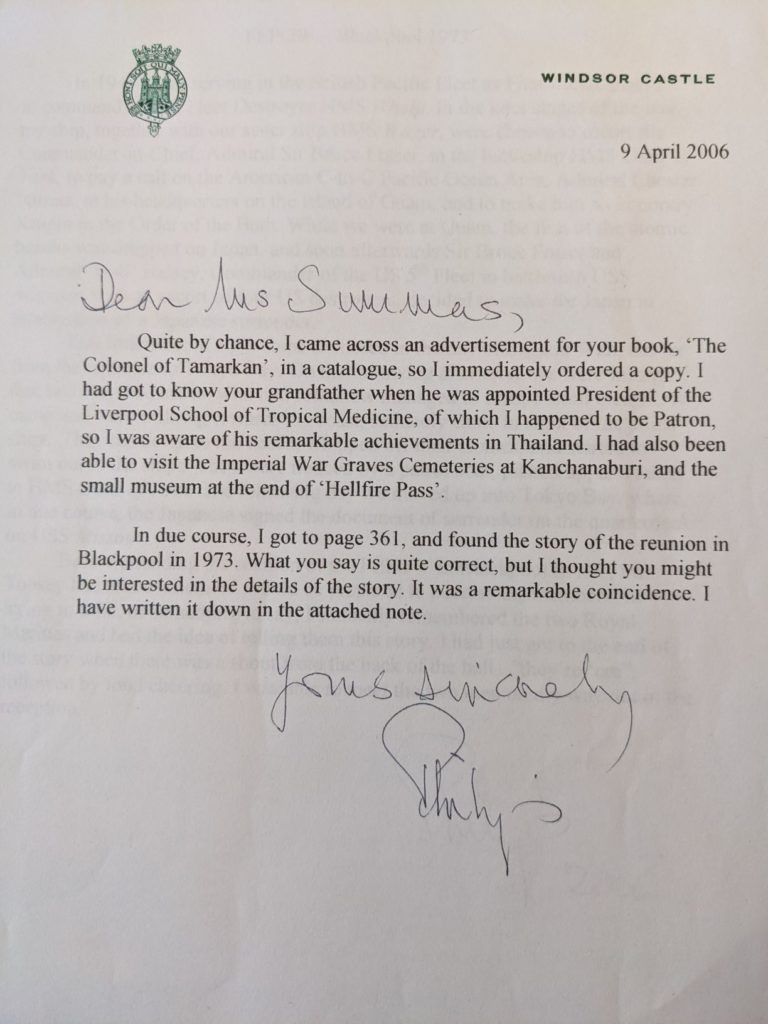

There is a PS to this story. Fast forward to 2005 and the publication of my book The Colonel of Tamarkan, the biography of my grandfather and his role in the construction of the bridges on the River Kwai. The book came out in October and the following April a very excited postman arrived at my door with a special delivery. The Duke had seen the book in a catalogue and had bought and read a copy. On page 361 I had written the story of the Blackpool FEPOW reunion of 1973 when my grandfather had hosted him at an event for 3,000 former prisoners of war. The Duke had a strong connection to the men as he and his ship had picked up two Royal Marines in August 1945. The two had been prisoners of the Japanese and had escaped from captivity in the final days of the Second World War. They spotted British vessels near the entrance to Tokyo Bay and immediately stripped off and swam out to safety.

The Duke told this story to the 3,000 men gathered in Blackpool and as soon as he finished a voice piped up from the back of the hall: ‘They’re here!’ The Duke and my grandfather made their way through a sea of excited men who cheered and clapped as the two former Royal Marines and their erstwhile rescuer were reunited. On that occasion the Duke spent so much time with the men that he had to leave for his next appointment without having met and shaken hands with the Mayor of Blackpool and other grandees. My grandfather was highly amused by that.

When I saw the postman this morning, we reflected with sadness that there would be no more recorded deliveries from Windsor Castle for me. But what memories.

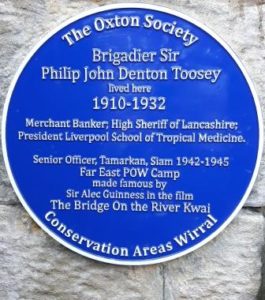

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

he transcript of a speech I gave to mark the unveiling of a blue plaque at the gates of the house where my grandfather lived in the early twentieth century. The people of Merseyside voted him the person most deserving of recognition. There was a huge turnout of Toosey relatives as well as two former prisoners of war, Maurice Naylor (96) and Fergus Anckorn (98) who unveiled the plaque. My son Richard read the words of the Japanese camp guard.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.

He was more than his title would suggest. His kindness, his delicious sense of humour, his repertoire of whistles and his passion for life never waned. He shared this passion with all who came into contact with him. To his friends he was Phil, and sometimes ‘Dear old Phil.’ To his wife, Alex, he was Philip with a particularly plosive P when she was cross with him. To his three children, Patrick, Gillian and Nicholas he was ‘The Captain’,named after Captain William Bush RN, a fictional character of extreme efficiency and loyalty in CS Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series. Thus to us his grandchildren he became Grandpa Bush. To his men he was the Colonel and later The Brig and to the thousands of people he met over the course of his working life he was simply Mr Toosey.