Pedal to Paris 2021 Day One London to Dover

121.31 km (75.38 miles)

1,296m (4,252 feet) ascent

5.15 hours

As we stood on the start line at Eltham Palace at 6:30 on a grey, chilly morning with mizzle, all the first-timers felt a sense of anxiety about whether we would make it to Paris at all. These were of course private thoughts, but I could sense them in the exchanges or silence between group members, while solo-riders looked nervous. Even the seasoned cyclists who have one, two, three or in the case of Paul Harding, 23 Pedals to Paris under their belts there was a sense of uncertainty about the ride to come.

We set off after soon after 7am and wove our way out of London, stopping and starting at lights, slowing and bunching to get around parked cars, dodging potholes and drains, manhole covers and cobbles. As we negotiated the M25 roundabout and set off into the lovely Kent countryside the speed picked up, we fell into small groups of riders and began to get the sense of moving together. It was nothing short of thrilling for me, who has only ever cycled with one or two other riders. At one stage six of us cycled for 10 miles without stopping, pedalling along at a comfortable pace higher than I had ever averaged in training.

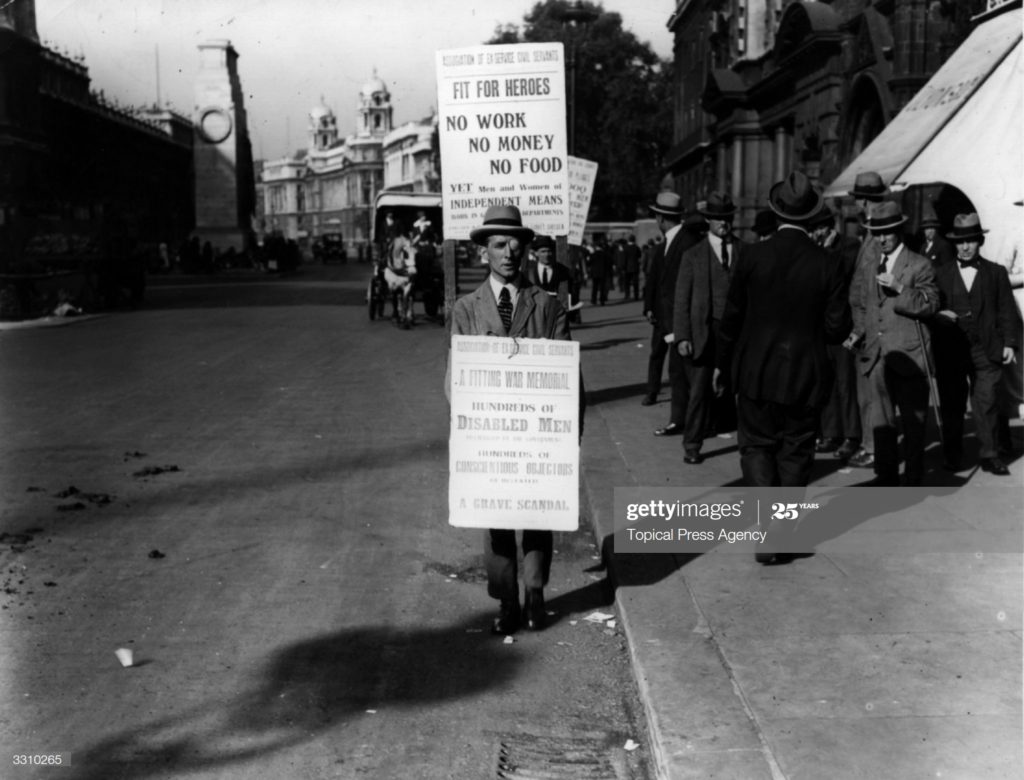

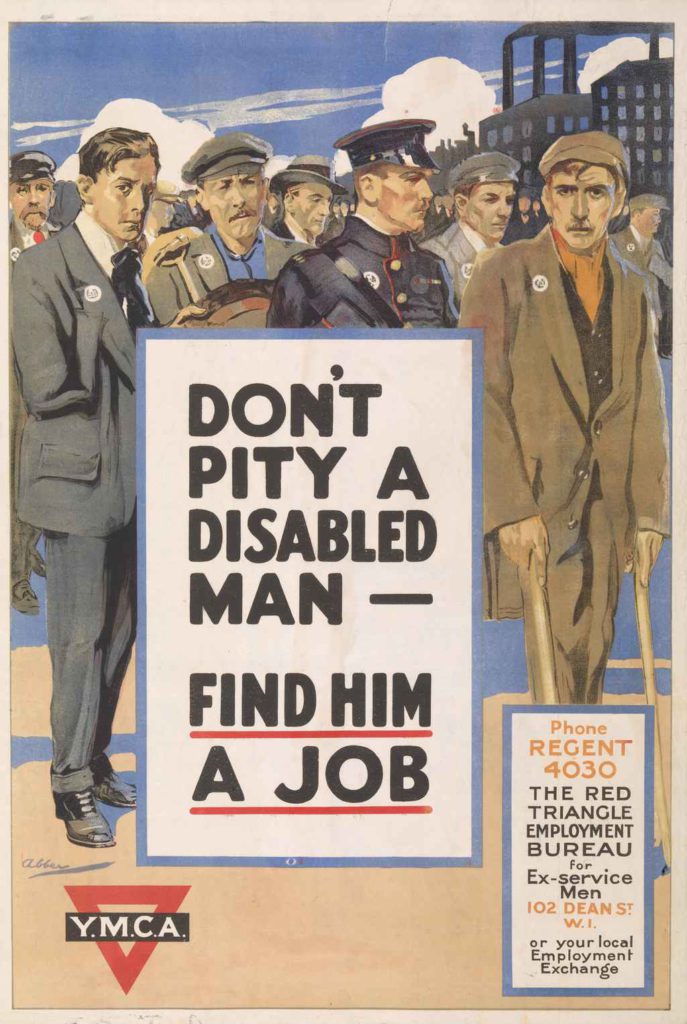

Our first stop was at the Royal British Legion village at Aylesford where we were welcomed by flag waving, cheering employees of the RBL and volunteers who served us coffee, sausage rolls, Vienna whirls and all sorts of goodies that in normal times I would not eat at 10 o’clock in the morning. That was a sign of things to come. Whenever we stopped anywhere en route we could be assured a fantastic welcome, sustenance, encouragement and some gentle ribbing.

Day One ended with a monstrous hill into Dover which nearly blew my thighs, such was the build up of lactic acid as we struggled at snail’s pace in Grannie gear up the New Dover Road to Capel-le-Ferne. 120m of climbing over about 0.75km. Unrelenting and painful. Our ride captains, a magnificent and talented group of cyclists who looked after us, encouraged us, helped when we fell off or fell back, were there on that hill, 65 miles into our first day, to help those who struggled up it. Two of them cycled up the hill four times. I took my hat off to them so often over the next three days.

Once we arrived in Dover we were ushered onto The Spirit of Britain and had a welcome supper of fish and chips with a beer to replace the much-depleted sugar levels in our blood, which Simon assured me was a good cure. Later we learned that the consumption of alcohol on the Tour de France was only banned in 1960. Not for health reasons but because it was believed to be a stimulant.

As we rolled off the boat and onto the quayside the enormity of getting here struck us all. It was nothing short of magical to step onto continental soil for the first time since the pandemic broke out 18 months ago. For most of us it was the first time abroad and the emotions were very close to the surface. We pedalled to the great Fort Nieulay and put our bikes into safe storage for the night and made our way to the hotels. Never has Belgian beer, which Simon, Chris and I found a nearby café, tasted so good.

Day Two Calais to Abbeville

134.42 km (83.5 miles)

1,234m (4,049 feet) ascent

6.15 hours

This began with the collection of bikes from the Fort and our introduction to the ISE (International Sport Event) team who were to accompany us from Calais to Paris. This team comprised four cars and a dozen motorcycles, the latter being ridden by ex-gendarmes who earlier this summer has escorted the Tour de France. I freely admit that I was over-excited about the outriders and chatted to them. They were warm, friendly and completely into their BMW bikes.

Our first ceremony was in Calais, soon after 8am. The Deputy Mayor, with special focus on sport, welcomed us to the town in a short speech which was followed by the laying of a wreath by Lieutenant General James Bashall CBE CB. Five minutes earlier I’d seen ‘Bash’ as everyone on the trip referred to him, in his RBL lycra. There he was in a dark suit laying a poppy wreath and speaking the Exhortation from Binyon’s poem For the Fallen. You know the words so well. ‘They shall grow not old as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.’ Alongside the general and the Deputy Mayor were two standard bearers: one from the town of Calais, the other from the Hertfordshire branch of the Legion. He, Paul, is the man who now has 24 Pedal to Paris under his belt and he does it on a recumbent bike with a huge union flag attached to a pole behind him. As the General finished the Exhortation, Paul repeated it in French. It was a powerful moment.

After the ceremony we gathered in front of the Town Hall where Lewis, our superb cheer-leader, organised us into three groups. The so-called Social Group would ride of first, followed 15 minutes later by Group 2 and 15 minutes after that Group 1 would sally forth. I had been advised earlier this year that Group 2 was a comfortable place to be as the speed was good but there was still time for conversation. Group 1 was for the super-speedy guys who wanted to ride in a proper peloton. The Social Group left at 9am and we divided into Groups 2 and 1. It looked as if everyone bar about six cyclists wanted to be in Group 2 so Lewis drew a line half way through the group and Chris, Simon and I ended up cycling with the back section which included the speedy guys.

Rolling out of Calais with our fabulous outriders halting traffic at every road junction was about as thrilling as it gets. Thirty of us poured in a liquid stream of cycling energy around corners, over crossroads, around round-abouts and out into the beautiful hilly countryside of the Pas de Calais. We were cycling over ground that had been trodden by millions of soldiers – both French and British – in the First World War and that just added to the sense of history that surrounded us all day.

The riding was great and the pace hot, which was fine until we hit a big hill and then I realised that what I saw as a wall the speedy riders saw as a minor rise. By lunchtime my legs were throbbing, and I decided that I wanted to be in a proper Group 2, not the souped-up version. Fortunately, others felt the same. Lunchtime was a buffet of baguettes made locally. We were told there were 37 different fillings on offer. They were delicious.

After lunch we went straight into the first hill, known in our ride brochures as Baguette Hill. We’d read about this in the forward planning emails but any amount of googling had left us none the wiser. It was only when we set off that we were told it was the nickname for the hill that came immediately after a lunch of baguettes on day 2 and that it was a test for us riding on full tummies. Predictably I found it very tough but soldiered on and spent the next 180 minutes riding some 72km (45 miles) without stopping. Our driver had failed to make the mid-afternoon break.

When we did finally stop in the beautiful village of Crécy-en-Ponthieu it took two ice lollies and three litres of water before I was able to concentrate on Dan’s short talk about the site of the Battle of Crécy in 1346, one of the earliest and most important battles of the Hundred Years’ War. From there we cycled as one group into Abbeville making the transition from countryside to urban streets with consummate ease thanks to our outriders. By now we all knew the commands for slowing down, speeding up, avoiding potholes. And then comes the ‘Stopping’ command. That was very welcome at the end of a long day.

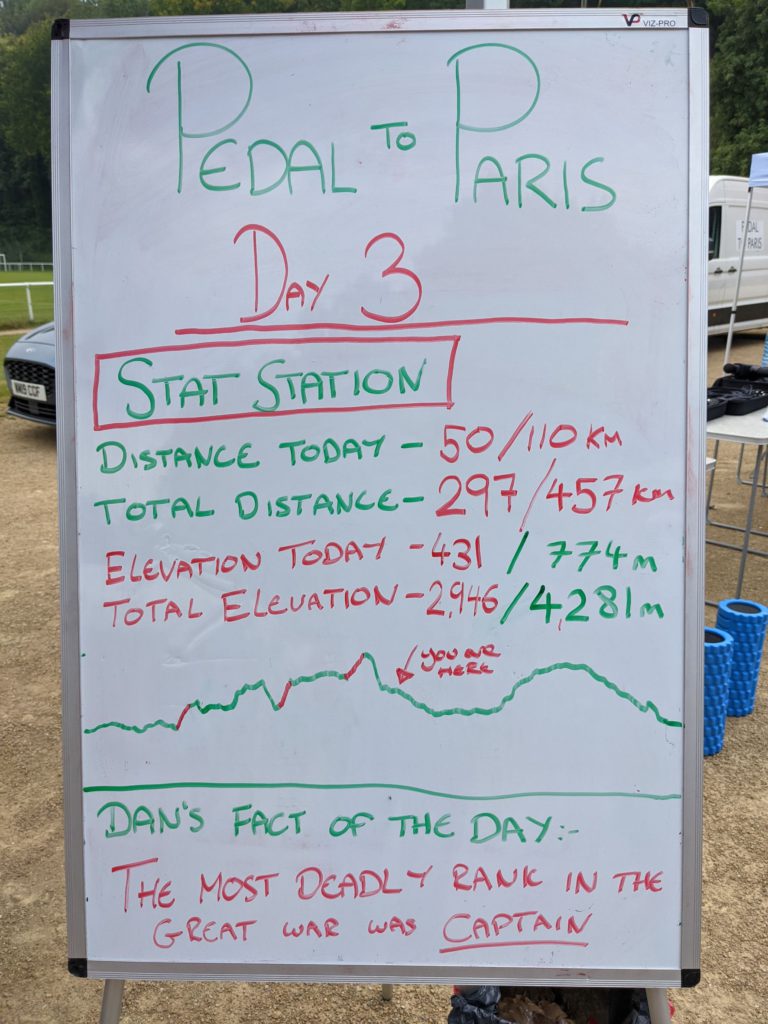

Day Three Abbeville to Beauvais

107.34 km (67.14 miles)

751m (2,467 feet) ascent

4.59 hours

The ceremony at the Abbeville War Memorial was attended by more standard bearers than the one in Calais. I was moved not only by the First World War standards but by those from the Second World War. One marked the ‘Prisoners 1939-1945’ which caught me out. France and Britain’s experiences of that war were poles apart. It made the wreath laying even more poignant.

We began the cycling with a steep climb which was painful on tired legs and I was glad I was in Group 2. The countryside was glorious: undulating roads through fields of corn, tobacco and sunflowers. Occasionally you would spot our tireless photographer disguised in a patch of sunflowers or lurking behind a signpost. His white motorcycle helmet was a giveaway and we always waved to him cheerfully even if our legs were burning at the top of a hill.

Our lunch spot on day 3 was in a sports stadium. There, on the sand, Dan created a reinterpretation of the Western Front during the First World War, using cyclists to represent the Allies and the Axis powers. He made them stand two steps apart and then talked us through every significant gain and loss on the Front. Each time one of them would be asked to step forward or back to mark a battle. What struck everyone was how little ground was fought over and what devastating losses and destruction resulted from that terrible war.

The make-up of the cyclists was biased heavily in favour of men. I’m not sure how many women there were but I would hazard a guess at about 10% (so 12-15 of us). That seemed to me to be not dissimilar from the make up of men to women in the First World War. We often forget how many women stepped up in both world wars to do their bit. On the Home Front from 1914-1918 hundreds of thousands of women worked in munitions factories and in men’s jobs on the trams, railways and in other roles. Then there were the female doctors, nurses, ambulance drivers and auxiliaries who worked in the dressing stations and hospitals in France and further afield in other theatres of the war.

In the Second World War women were active in uniform, albeit at a distance from the fighting. They worked on radar, on coding at Bletchley Park as well as nurses and ambulance drivers. Some flew planes from factories to airfields. And a sizeable number worked with the Special Operations Executive. I thought the story of Nancy Wake, known by the Germans as the White Mouse, might inspire the women cyclists. She was part of the French Resistance in Southern France during the battle for the liberation in 1944. Desperate to file a report for SOE HQ in London, but unable to make contact via radio, Nancy Wake grabbed a bicycle and claimed to have ridden some 172 miles in 24 hours. She said afterwards: ‘That part of my anatomy which is meant to give pleasure was on fire. I could neither sit nor stand for two days.’ That chimed with some of us. Imagine doing that distance on an old-fashioned bike without gel shorts, comfortable cycling shoes and under the constant threat of attack.

After lunch, and the inevitable steep hill to concentrate the mind, we sped across the countryside to the village of Auchy-la-Montagne where the village (population c. 570) had put on a magnificent welcome for us. As we entered Auchy we saw signs saying: ‘Welcome English Friends’ and ‘Auchy is Happy to Meet You.’ As we rounded the corner into a little area next the park and opposite the Mairie we saw gazebos with tables laden with cups of local wine and sweets, while members of the village’s veterans’ association waved us in, some holding flags.

This lovely village has welcomed the Pedal to Paris caravan every year and this time they presented the President with a huge cup to mark the 25th anniversary. The mayor was unable to attend but his representative told the story of the liberation of Auchy-la-Montagne in 1944 by the British 8th Army. The mayor is known to have said in the past: ‘we prefer you on your bicycles than in tanks.’ Two children were on the local council to give their age group a voice in local politics. They made a request to the RBL: could we find them an old-fashioned British telephone box that they could use as a library for book exchanges in the future. The general threw down the gauntlet to the cyclists to see if anyone could help. Let us hope someone can.

With hearts warmed by the welcome and the excellent rosé we pedalled off as a group to Beauvais for a ceremony at the war memorial. There was a sizeable crowd gathered in the park around the memorial already and we saw standard bearers from several veterans’ groups with a gap for Paul Harding. Like the General, Paul made a lightening change out of his lycra and into the uniform of an RBL Standard Bearer.

The Mayor of Beauvais made a speech in French and English. He spoke of the collaboration between the Allies in the First World War. We had already been reminded by Dan that the French lost more men in 1914 than the British did in the entire war. Here we were, facing the Beauvais memorial, contemplating that appalling statistic. The mayor then talked about the Second World War when Beauvais had been invaded by the Germans. The British 8th Army liberated the town on 30 August 1944 and the mayor expressed the town’s enduring gratitude to their liberators. It was a humbling moment.

Beauvais had been extensively damaged during both wars and much of the older part of the city was all but destroyed. The cathedral was rebuilt in the ensuing years and as we cycled past it after the ceremony it was hard not to be moved by the resilience of this magnificent city.

Day Four – Beauvais to Paris

96.86 km (60.18 miles)

883.92 m (2,900 feet) ascent

4.40 hours

The final day of the ride seemed to entail a lot of climbing. The weather had warmed up and it was with some considerable relief that we cycled into the aptly named village of Menucourt for our last baguette lunch of the ride. From there we set off as a single group for the last 40km (25 miles) to Paris. We were given strict instructions not to attempt to overtake other cyclists on this leg and to follow the car as closely as we could, especially once in Paris.

This was the moment when the motorcycle outriders were at their most brilliant. The closer we got to the capital the greater the number of cars on the roads and the larger the junctions. Sometimes we found ourselves streaming down the slow lane of a dual carriageway with cars zipping past us at high speed, but never once did we feel vulnerable. Our outriders had our backs and motorists who did not play fair were subject to gesticulations and whistles to keep them in place.

Entering Paris via St Germain-en-Laye, which occupies a large loop of the River Seine, we were now less than 20km from the Arc de Triomphe. This lovely suburb has a surprising link to the United Kingdom. In 1688 James II, King of England and VII of Scotland, exiled himself to the city where he remained for the final three years of his life. We crossed the Seine for the first and second times and headed towards the city centre itself. As we rounded the Place de la Porte Maillot we shouted ‘cobbles!’ Suddenly we were on the Avenue de la Grande Armée and there, in the near distance, the Arc de Triomphe. Tired legs, sore backsides, aching arms and bruised feet all vanished as we sped up the cobbles towards the Arc and over to a layby next to Avenue Foch.

Lewis and the wonderful RBL team greeted us with cheers and whistles ushering us to safety and towards a table with bottles of beer. It was a remarkable feeling and I am not sure I remember seeing so many smiling sweaty faces on one small patch of ground as I did that afternoon. We parked our bikes, took endless photographs and then made our way over the Avenue Foch to a tunnel which led us under the Charles de Gaulle Etoile and the entrance to the Arc de Triomphe itself. Currently the monument is in the process of being wrapped up for a Christo installation which gave it an even more wonderful air of grandeur.

As we lined up in two rows either side of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier I had to blink hard not to let roll the tears of overwhelming emotion. Bash had once again, and for the last time on this trip, donned his dark suit and morphed into Lieutenant General James Bashall CBE CB, President of the Royal British Legion, which marked its centenary in May 2021. A representative of the mayor’s office gave a speech about the significance of the Unknown Soldier, the idea for which predates our British Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey by four years. This soldier represents the silent voice of all those lost in war and of Remembrance. Behind us we could see the Champs Elysées, the glorious rooftops of Paris and above us the blue sky and sunshine that had accompanied us all that last day.

After the wreath-laying we sang the National Anthem and the Marseillaise, whose words we had all learned (a bit) over the last few days. And then it was over. A girl standing next to me asked me to tell her what the French official had said in his speech. As I explained what it all meant the tears began to flow. I could not stop them. Everything about the ride, from the moment we conceived of the possibility of doing it, through the long hours of winter training, to the uncertainty of whether the RBL could even stage the ride given the pandemic, to the glorious moment at lunchtime on that day when I realised I, we, were going to make it. I have not cried like that for a very long time. We had witnessed something very special and each of us had gained a personal achievement.