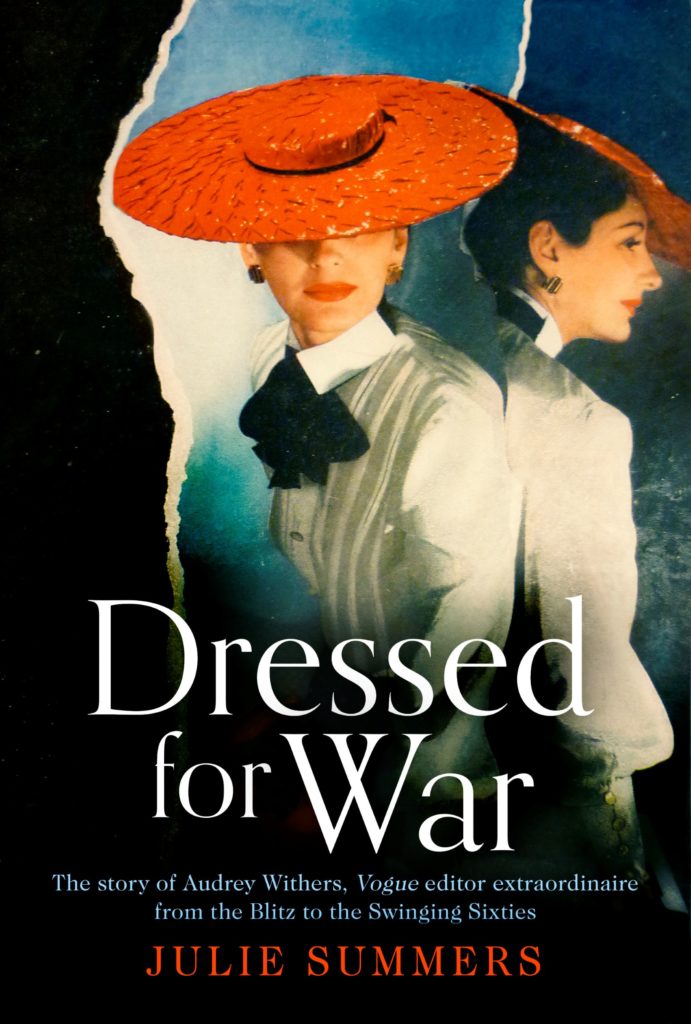

Several people have asked me what Audrey Withers’ reaction to the current crisis would have been. I have thought about it a lot and it occurred to me that it might be interesting to compare 1940 and 2020.

At the beginning of the Second World War the government closed down the country. It banned all public gatherings, sporting events and race meetings. Theatres and cinemas were ordered to close and no group meetings of more than 100 people were permitted anywhere except at church. Does this sound familiar? The introduction of petrol rationing from midnight on the day war was declared and the blackout altered people’s lives even more directly. The shutdown lasted for just twelve days but it had the effect of changing people’s behaviour, the way they thought about being at war – even though the war proper did not affect them until the spring of the following year – and it changed the way people moved around.

Now, in 2020, we are in equally uncertain times but on this occasion we are not terrified of air raid or gas attacks but of an invisible virus. The government is not only protecting its citizens but our wonderful, precious but horribly overstretched NHS.

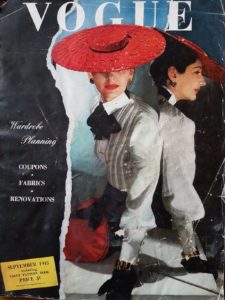

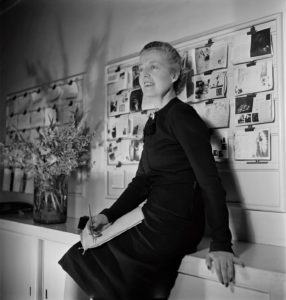

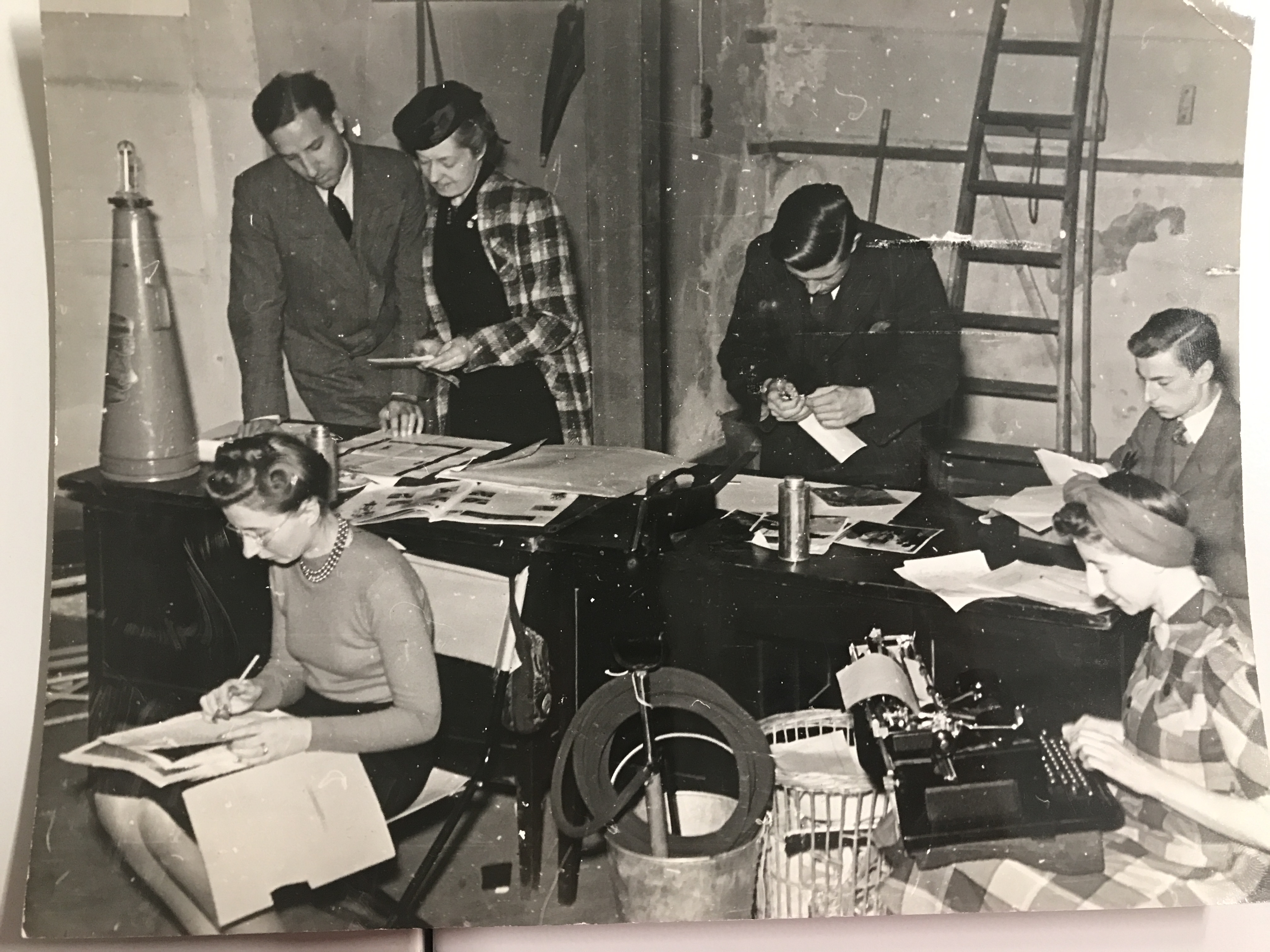

So what would Audrey have done? The answer depends of course on what period of her life we are going to imagine in this hypothetical situation. Let’s place her in London at the beginning of the Blitz, days after she has been named as editor of Vogue, when nightly air raids and daily warnings disrupted life in so many ways. Audrey wrote an article about living under those conditions for American Vogue. She described how every night she and her editorial and art staff packed up a large laundry basket with all their ‘treasures’ and every morning the basket was unpacked and work began again. ‘If the siren goes work goes on until the alarm warns that planes are overhead or that guns are firing with the result that we now take shelter less frequently but more rapidly.’

I find in here a hint of how in the very early days of the Blitz there had been a touch of panic but by early October, when she wrote this article, she had got used to the bombing.

We grab work and paraphernalia, descend six flights of stone stairs to the basement. We look as if we are going on a peculiar picnic: coats slung around our shoulders; attaché- cases with proofs, photographs, layouts, copy, mixed up with gas- masks, sandwiches and knitting. The Art Department men carry under one arm a stack of drawings and layouts; and under the other, a stirrup pump, a pick axe or a shovel. It’s a peculiar picnic all right.

She described how they greeted each other every morning with ‘what kind of night did you have?’ and how gallows humour soon emerged and kept them sane even when the news was grim. ‘A feeble joke makes us laugh, and we’re glad of the chance to laugh at anything; and on the other hand, you get oddly insensitive and callous, and are amused by incidents that normally you would have found macabre.’ She concluded the article by saying that they lived day by day, not looking too far ahead but always trying to be organised and practical.

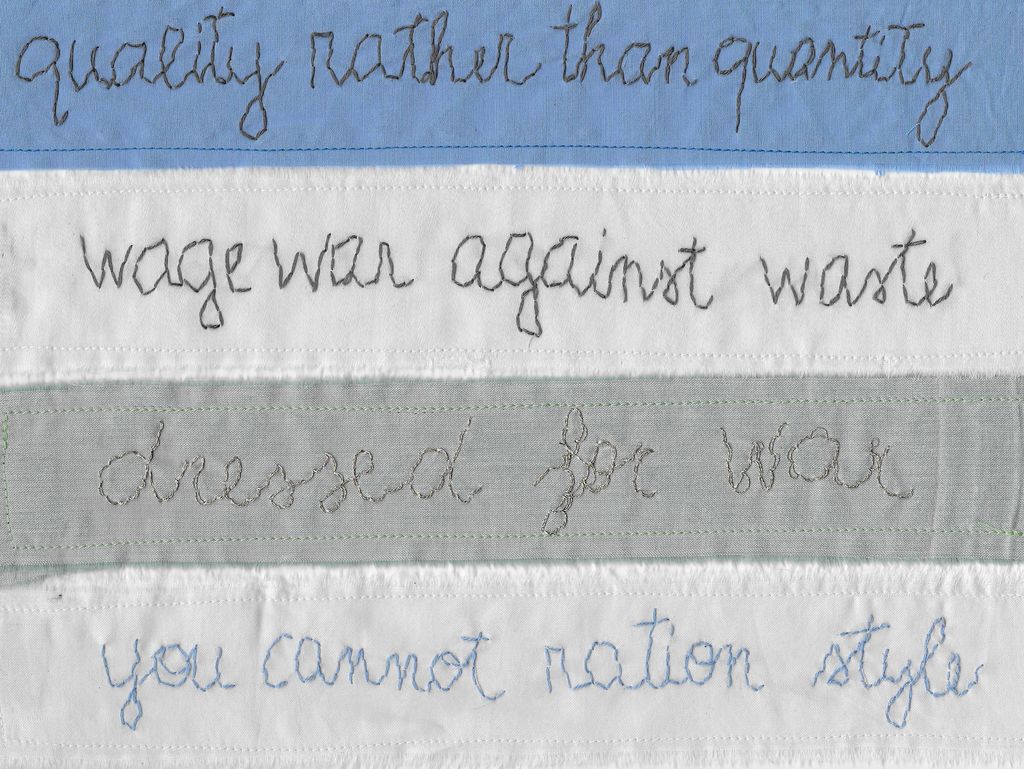

It would be wrong to paint Audrey as instinctively brave. She was not courageous like her fearless photo-journalist, Lee Miller, but she became brave through sheer hard work and a determination to keep going under any circumstances and she was organised. Another aspect of her personality was her deep and furious dislike of cheating of any sort. She railed against people who bribed shopkeepers to give them a little bit extra over the ration and she despaired about Vogue readers who cheated with their clothing coupons. I suspect she would have had something to say about panic buying and, worse still, the scalpers who clean out supermarket shelves and then offer the products for sale at a higher cost. Spivs are what those people were called during the war and Audrey despised them.

She was a caring person and I am sure that she would have worried about people being lonely and cut off. There was no compulsory self-isolation during the war but petrol rationing had more or less the same effect for people living in the countryside. Her parents, both in their seventies, had been socially active in the nineteen twenties and thirties. By 1940 they were living on the edge of a small village outside Banbury seeing almost nobody week in, week out. They were lonely and depressed by her father’s ill health. Audrey and her sister, Monica, tried to ensure they had visits or letters as often as circumstances permitted.

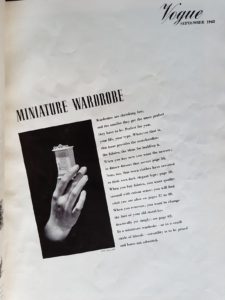

As we are today, so Audrey was overwhelmed by government advice. During the war it was called propaganda and it was sometimes issued three or four times a day. The Board of Trade published nearly 200 notices in one year on the subject of women’s underwear alone. The ministries of food, agriculture, health and so on were equally busy bombarding editors with information. Audrey had to decide what to publish in Vogue, a monthly magazine, and what could be ignored as it had already been dealt with by the daily press.

By the end of 1940, when London had been bombed for 56 nights consecutively, Audrey could be proud that she had managed to get the October, November and December editions of her magazine out almost on time. November had been two days late and December just one. One of her staff, Audrey Stanley, wrote to Condé Nast describing how they had coped during those difficult months:

We went through such a transitional stage and we did not know exactly what to strive for as everything was so precarious and atmosphere and feeling was as fickle as the wind, but now I really think a comprehensive pattern has come out of it all. Audrey Withers is a remarkable person. She has such balance and tact and we all admire her enormously as being editor just now must be a difficult job.

As the war went on, Audrey became more confident in her role as editor and more impressive in the way she coped with the pressure. In 1944 the President of the Board of Trade, Hugh Dalton, described her as the most powerful woman in London.

If we can take a message from Audrey’s strategy for coping in difficult circumstances I suggest it would be to keep calm and play fair. And, if you fancy, wear a hat.