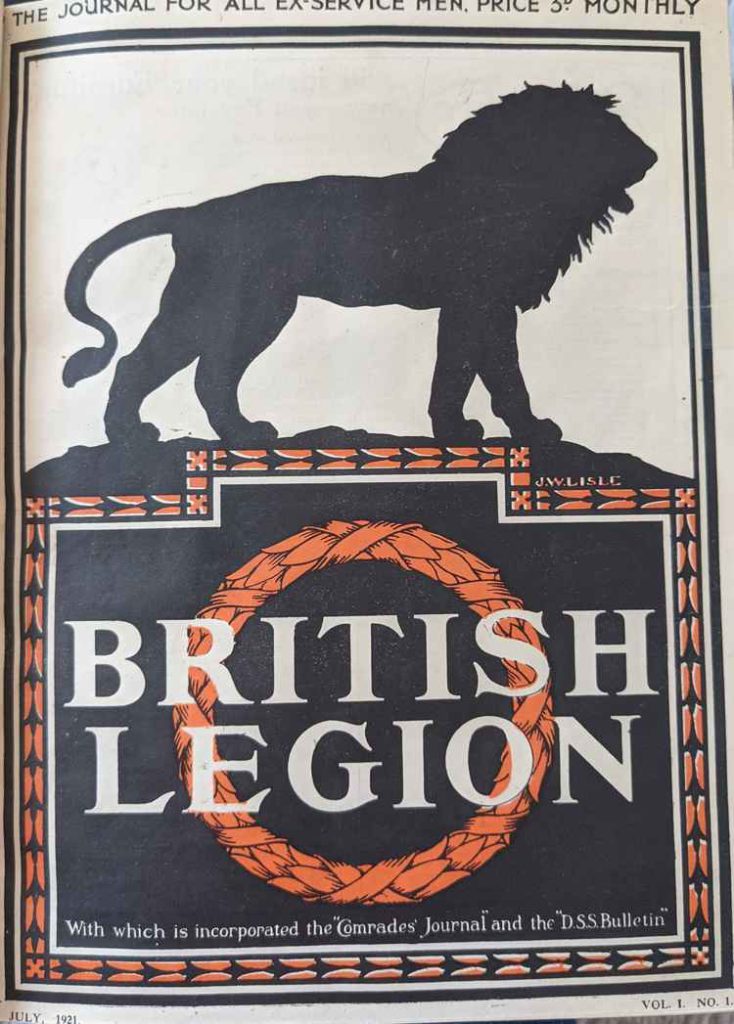

Two months from now, on 15 May 2021, the Royal British Legion will celebrate its 100th anniversary. Born out of the ashes of the First World War, the Legion was the amalgamation of several ex-Services organisations, all fighting on behalf of those wounded, disabled, widowed or orphaned by war. Over the last century the Legion has become part of the British cultural landscape. Remembrance and the Poppy are its most recognisable features but there is so much more to this great organisation as I discovered while working on a book for its centenary. I am going to celebrate the RBL in a monthly blog leading up to 15th May with a few behind-the-scenes stories.

In October 2019 the Royal British Legion commissioned me to work on a book to be published in May 2021. Of course I had no inkling that I would have to write it under pandemic conditions. When the first lockdown was introduced in March 2020 many people assumed that writers had never had it so good. With no distractions such as travel to book festivals or teaching commitments, we were surely in a uniquely wonderful position to write. Weeks, possibly months of forced isolation stretched ahead – a writer’s dream. As with so many dreams, the reality turned out to be very different. Living in forced isolation was one thing, but being deluged by grim headlines and worse death figures daily, plus the lingering fear of an invisible enemy in our midst, it was far from the utopian quiet that writers crave.

But I had a deadline. The first draft of my book was due to be handed over to the publishers in September. My problem was that from early March I had no access to Haig House in London’s Borough High Street, where the Legion’s archive material is stored. Nor could I get to libraries or Legion branches. Everything would have to be done remotely and that required a radical rethink of my usual working methods. Those who know me well are aware that I am happiest when ferreting around in old paper files, reading last century’s news and talking to archivists whose passion it is to preserve our nation’s memory.

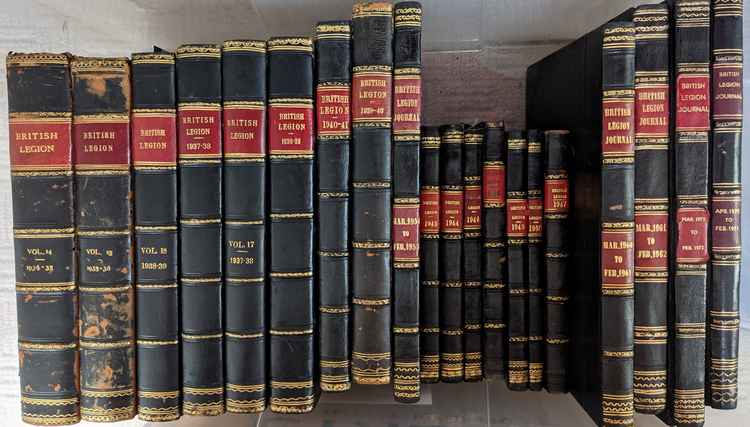

One stroke of luck occurred in late May when it was briefly possible to gain access to Haig House. I was able to procure a number of bound copies of the Legion’s Journal, their monthly magazine, dating back to 1921.

I could not have the full set so I was invited to take a stab at the years I thought would be of greatest significance to me. Quite the challenge so I chose 32 volumes between 1921 and 1972 which included anniversary years 1931, 1941, 1951, 1961 and 1971 as well as all the volumes from the Second World War, which were tiny owing to the shortage of paper. There was also an important photograph album from the Legion’s peace visit to Germany in 1935 which I also requested.

The operation to secure this valuable material was undertaken in the form of a heist. My officer son was dispatched to Haig House to collect the journals and was alarmed to be handed a large red album with a swastika on the front. Being inscrutable he did not flinch, but he did express his surprise when he arrived home in Oxford with his precious cargo. With the exception of one or two volumes that might have been useful, these monthly magazines in their beautiful leather bindings, gave me as much information as I could possibly have needed for the potted history of the Legion I had been asked to write.

What I had not expected from the Journals was the rich picture they offered of life in Britain in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, especially for those disabled by their war service. Yet these magazines were far from depressing. They were uplifting. The energy behind the early founders of the Legion was remarkable and the men and women who worked as grass roots level in the branches that sprang up around the country no less so. This was a young man’s organisation. The Legion’s first chairman was in his early thirties, many of the men on branch committees in their twenties. They were not grandees – although Field Marshal Haig and Edward, Prince of Wales gave the leadership clout with the government when needed – they were ordinary men and women who cared passionately about making post-First World War Britain a better place. And help was much needed.

Over 6 million men had served during the First World War, of whom 1.1 million were killed, including 350,000 from overseas, and some 1.75 million wounded. Of that latter number over half were permanently disabled. Widows, orphans, families of the wounded, the disabled and the unemployed all needed the Legion’s support. At that stage, the Legion estimated it had responsibility for up to 20 million people and it relied, in the main, on its volunteer army of members and officers to carry out the welfare help required.

The Royal British Legion is an organisation with a big heart and it has been the joy of writing this book to lift the lid on the myriad ways the Legion has made so many people’s lives better. From facing down the government on pensions and war disability payments to helping veterans with physical and mental health problems the Legion never gives up. It works day in, day out and the work it does really matters. It saves lives.

Over the next weeks and months, you will read and hear a lot about the Royal British Legion as it celebrates its centenary. I am very proud to have been a part of sharing that story, particularly the early years when the vital groundwork was laid. Watch out for my next couple of blogs when I will lift the lid on some of the less well-known aspects of the organisation most of us think of only around Remembrance Sunday.