Welcome to my 13th newsletter. I’m shocked to see that I have not sent a letter out since January of this year, although I have been using www.facebook.com/Jambusters1 to mention the odd thing that is going on with the book. This book came out on 28 February 2013 and has been studiously ignored by Radio 4, all the mainstream press and the Daily Mail, who bought the serial rights but never ran it. However, the sales have been more than healthy thanks to the grapevine and the WI, who have embraced the book wholeheartedly. So thank you to everyone who has been so supportive.

Despite quiet on the review front, I have never been asked to do so many talks and events. I have spent at least one, and often two or three, days a week going out and about, lecturing about Jambusters and other projects, so I have not been slothful. However, the main part of my written work since the book came out has been for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission project.Contents

- A Grave Matter

- Mountain Matters

- Beauty on Duty

- Pen Thoughts

- Forthcoming Events

Scartho Road Cemetery, Grismby, war plot with the newly installed panel on the left © CWGC

Scartho Road Cemetery, Grismby, war plot with the newly installed panel on the left © CWGC Kilchoman Military Cemetery on the Isle of Islay © CWGC

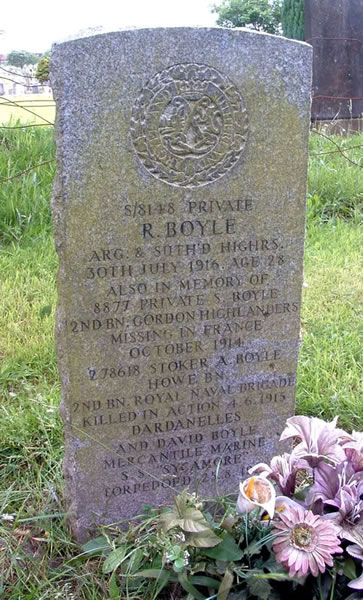

Kilchoman Military Cemetery on the Isle of Islay © CWGC The Boyle headstone, Glasgow Lambhill Cemetery

The Boyle headstone, Glasgow Lambhill Cemetery

© The Scottish War Graves Project Doug Scott and Chris Bonington (left) crawling down the Ogre ©Doug ScottA Grave Matter

Doug Scott and Chris Bonington (left) crawling down the Ogre ©Doug ScottA Grave Matter

A year ago the Commission (CWGC) asked me to write Visitor Information Panels for 100 of their UK cemeteries. I know I have mentioned this extraordinary fact in previous newsletters but it bears repeating. There are 23,000 CWGC cemeteries and memorials in 153 countries worldwide. Half of all those sites are in the UK and the only country in the world that has more burials is France. Some 170,000 servicemen and women are buried in the UK. Why, you might ask? Well, it has been my job to find out and tell people, and the reasons have been far more interesting and diverse than I would have thought possible. Some died of wounds sustained on the Western Front, at Gallipoli or further afield. Others died of disease or in training accidents. Many Second World War burials are Air Force or Navy, both Merchant and Royal.

I am constantly amazed, as I take on new cemeteries for research, just how much of the social history of an area is caught up in the stories of the servicemen and women who died and are buried in war graves. The First World War, in particular, changed the history of towns and villages throughout the United Kingdom. Take Grimsby for example. There is a stunning war plot in Scartho Road, a huge municipal cemetery in the centre of the town, with 200 Second World War burials but the 281 First World War burials dispersed throughout the cemetery. Why are they scattered? They are the graves of men who died and were buried in family plots at the request of their relatives. The majority of them are local men who were part of the fishing fleet that became the first auxiliary patrol, hunting for mines and submarines off the East coast. There were 880 vessels and 9,000 men from the Humberside fishing trade patrolling the waters. A large proportion of the fleet was lost.

Then, on 18 August 1915 the E13 submarine was blown up by a German destroyer in Danish waters. Fifteen men died in the incident and their remains brought back to Hull 10 days later to be transported to their home towns the following day. One observer wrote: “The scene of the fifteen coffins, draped in the Union Jacks, each with its own hearse and drawn by black horses passing through Hull city centre, while thousands thronged the route to Paragon Station, was described as one of the most moving of the war. One was that of a local man, Herbert Staples, who was laid to rest here at Scartho Road.”

On the Isle of Islay there is a cemetery called Kilchoman with 73 graves in the corner of a large plot. It turns out that the cemetery originally contained the remains of 300 American soldiers as well as the 73 British sailors. These soldiers had been on their way to the Western Front in February 1918 when their ship, the Otranto, was involved in a collision in dense fog and more than 400 drowned. After the First World War, the soldiers were all moved either to the US or to the US cemetery at Brookwood. Only the graves of the sailors remain.

I can cope with the big stories and the social history. Where I come unstuck is when I find a family story that is particularly heartbreaking. While I was researching Glasgow Lambhill Cemetery I came across a headstone with the names and dates of death of four men from the same family. Private Robert Boyle, the youngest, is buried in Lambhill, having died of wounds in hospital in July 1916. He was 28 and I guess he was injured on the Somme. His three brothers are all named on the headstone but died elsewhere. Samuel Boyle died in October 1914 and is commemorated by name on the Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres, so he must have been involved in First Ypres and his body never recovered. The next brother, Alexander Boyle, is commemorated on the Helles Memorial on Gallipoli. He died in June 1915 and similarly, his remains were never identified. And then the oldest brother, David Boyle, died in August 1915 when his ship was torpedoed. He was a member of the Mercantile Marine and was 49 years old. His name is on the Tower Hill Memorial in London. How does any mother recover from that kind of horror?

It sounds, perhaps, a bit of a miserable job to write about these cemeteries but it is not. It is hugely uplifting to think that their graves are still so beautifully cared for almost 100 years after they died. The Commission is an impressive and caring organisation and I feel very lucky to be working with them. 48 completed, 52 to go.Mountain Matters

The Mountain Heritage Trust, of which I have now been chairman for three years, has begun to flourish. For the last six or seven years it has been dogged by financial worries and underfunding. However, a growing relationship between Mountain Heritage and the National Trust is changing people’s perception of what we can achieve. We hope it will lead to MHT exhibitions and displays in a small number of NT properties in climbing areas such as Llanberis, the Peak District and the South West. Mountaineering and climbing has some of the most spectacular imagery and a good number of captivating stories to tell, so we are delighted to be able to have a larger platform to bring these to the attention of the public.

Meantime, this autumn I am organising a fundraising dinner in London called A Night on the Ogre with two of Britain’s most famous climbers – Chris Bonington and Doug Scott. On 13 July 1977, just after dusk, Chris and Doug reached the summit of the Ogre, in Pakistan. It stands 7,285 metres, a height where the amount of oxygen in the air is just half of that breathed at sea level. Recognised as the hardest rock climbed at that altitude at the time, it was a monumental achievement and it was twenty-four years before it was climbed again.

After the sun had set Doug was making the first abseil off the summit and slipped on verglas and broke both his legs near the ankles. Four days later, during another abseil, Chris smashed two ribs. Altogether the descent took eight days, with Chris and Doug fighting for survival. Crawling off the Ogre in a blizzard with just two fellow climbers, Mo Antoine and Clive Rowland, to assist them, and no food for five days, resulted in an epic tale of strength and determination against all the odds.

This escape has taken its place amongst the legends of mountaineering history and I believe it will be a terrific evening in October. MHT keeps me on my toes and takes up far more of my time than it really should, but with stories like this to be told, I cannot really complain.Beauty on Duty

Utility Underwear from a wartime collection belonging to Eve DaviesI am never completely happy when I haven’t got a good book project on the go, so I was genuinely excited and thrilled to be asked to write a book on the history of wartime fashion for Profile Books. It will be published in time for an exhibition on the same subject at the Imperial War Museum in Spring 2015. The IWM will be closely involved in the project and I hope their historians will help me to avoid clangers about seams, stitching and styles. Those of you who know me well will smile at the idea of me writing about fashion. I am definitely not fashionable. But I have been brought in to look at the social history side of wartime clothing, hair styles and the like, so it should be a great fun project and I cannot wait to get my teeth into it.Pen Thoughts

Utility Underwear from a wartime collection belonging to Eve DaviesI am never completely happy when I haven’t got a good book project on the go, so I was genuinely excited and thrilled to be asked to write a book on the history of wartime fashion for Profile Books. It will be published in time for an exhibition on the same subject at the Imperial War Museum in Spring 2015. The IWM will be closely involved in the project and I hope their historians will help me to avoid clangers about seams, stitching and styles. Those of you who know me well will smile at the idea of me writing about fashion. I am definitely not fashionable. But I have been brought in to look at the social history side of wartime clothing, hair styles and the like, so it should be a great fun project and I cannot wait to get my teeth into it.Pen Thoughts Bill Drower at the old Toosey family home in Birkenhead for the launch of The Colonel of Tamarkan in 2005

Bill Drower at the old Toosey family home in Birkenhead for the launch of The Colonel of Tamarkan in 2005 Mattie (left) and Tiggy, my constant companions in my office. They have a wine box each and show no interest in my writing whatsoever.

Mattie (left) and Tiggy, my constant companions in my office. They have a wine box each and show no interest in my writing whatsoever.

Next month my literary agency, Felicity Bryan, celebrates 25 years in the business. It is a fabulous achievement. So when I was on a recent cycling holiday in Devon, I took the time to write to my agent to offer my congratulations and thanks for a very creative partnership that has lasted nearly a dozen years. I wrote by hand, as I always try to do with personal letters, and she told me she received the letter with trepidation. A hand-written envelope is often a harbinger of bad news. That got me thinking, because in my line of work, a hand-written envelope invariably means someone of the older generation writing to me with comments or, if I’m very lucky, a story.

My all time favourite hand-written letter came from Bill Drower, who had been in a prisoner of war with my grandfather in the Far East. Towards the very end of the war he had fallen foul of the psychopathic camp commander, Noguchi, and had ended up being imprisoned in a hole in the ground for 77 days. Oxford educated, a gentleman to the core, Bill never held a grudge against the Japanese for his torment and his letter to me opened thus:

“My dear Miss Summers, My name is Captain William Mortimer Drower and your grandfather was kind to me when I got into a spot of bother in the camp gaol…”

After that initial contact in 2003 I got to know Bill quite well and I count it as one of the great privileges of my life to have met and spent time with this remarkable man. The last time I saw him he was short of breath but still full of vim. I had my youngest son with me and Bill challenged Sandy to a game of chess. They played on a board that had been dropped into his prison camp by the RAF in 1945. Sandy was a good chess player but Bill beat him soundly. Three weeks later he had a fall and died. When I told his daughter, Sarah, the story of the chess match she said she was amazed. He had not played chess since 1945, although he had kept that board as a memento of his time in the POW camps.

I have kept all 23 of his hand-written letters in their hand-written envelopes. To me they are anything but bad news.

Julie Summers

August 2013, Oxford