Where were you born? I think it is fair to say that most people know their place of birth and probably the name of the hospital, maternity home, house name or number where they came into this world. Thinking about it, though, it is in some sense a strange question because chances are you have no personal knowledge of the place and you have probably never returned. Is it not a little unusual to imagine that you might meet up with people who were born in the same place as you? And further more to do so annually and in great numbers? I was born in Clatterbridge Hospital in Birkenhead and not far from Liverpool but I have never met anyone in my life, other than my siblings, who was born there. Two of my sons were born at the Rosie Maternity Hospital, now the Rosie Hospital, in Cambridge and as far as I know they have never met anyone else born there either. So how extraordinary was it for me to visit Brocket Hall last month and to meet over fifty people who were born at the hall when it was a maternity home between 1939 and 1949?

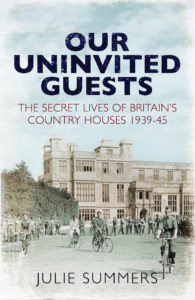

The story of the Brocket Babies features in chapter one of Our Uninvited Guests and it is a remarkable story in so many ways. At the outbreak of the Second World War Brocket Hall belonged to Arthur Ronald Nall Cain, the second Lord Brocket, a well-known Nazi sympathiser. He was so close to the German Foreign Minister in the nineteen thirties that one of the bedrooms in the hall was renamed the ‘von Ribbentrop Room’, though it has since reverted to its previous name, the Queen Victoria, because she liked to stay in that modest but luxurious bedroom when she visited the hall in the mid-nineteenth century.

Brocket Hall has one of the most colourful histories of any of Britain’s country houses from royal love affairs, mad wives and illegitimate offspring to a healthy dose of society intrigue. In the nineteenth century the hall had been in the possession of two prime ministers: the Lords Melbourne and Palmerston, the mother of the former having been lover of the Prince Regent, later George IV. Naturally enough there is a room named after him too: the Prince Regent Suite. So how glorious from a historian’s point of view that this house, with its walls hiding past scandals, was taken over by the Red Cross and used as a maternity hospital for a decade at a time when childbirth was clinical and married women held up as paragons of virtue.

There are photographs of mothers in the Prince Regent Suite sitting up in metal-framed hospital beds knitting white caps for their babies, attended by nurses in crisp white uniforms set against the background of the sumptuous Chinese design hand-painted silk wall-paper chosen by the Prince Regent for the room in which he would entertain Lady Melbourne. Not so however for those poor girls who found themselves carrying a baby conceived out of wedlock: they belonged to a class of woman to be condemned and whose babies would be taken away immediately after birth. Those whose families could afford to pay would send their daughters to Lemsford House, just outside the gates of Brocket Hall, where they were held until it was time to give birth in the delivery suite in the hall. Those who could not afford to pay were sent to Brocket Hall and worked below stairs in the kitchens and cellars. They were known as the Brownies. It is not clear from the records how many Brownies worked at Brocket Hall during and after the war but it would have been scores, if not hundreds. I found it a sad and chilling reminder of society’s relatively recent attitude towards illegitimacy. Indeed when I was growing up in the mid-nineteen seventies and a school friend of mine fell pregnant she was considered to be ‘in disgrace’ and her baby was delivered and adopted immediately. But she never returned to school.

In all, 8,388 babies were born at Brocket Hall including several pairs of twins. At the last count the couple who organise the Brocket Babies website (www.brocketbabies.org.uk) have a mailing list of over 1,100 ‘babies’ who were born there between September 1939 and November 1949. That is more than one in eight of all the babies. I find that fascinating.

Why does it matter to them where they were born? They could not possibly remember anything of Brocket Hall as they would have left with their mothers to go home, or with the Church of England Adoption Agency, after two weeks. But matter it does and it is clearly an essential part of who they are today. I believe it gives them a sense of belonging to an exclusive community whose existence was called into being by an event in history that none of those born at Brocket Hall experienced in person, namely the outbreak of the Second World War. But their mothers did. Each and every one of them lived through the war and but for the decision of the Ministry of Health to move expectant mothers out of the cities for their safety, all of them would have given birth in the City of London Maternity Hospital. It is one of the many strange juxtapositions of the Second World War.

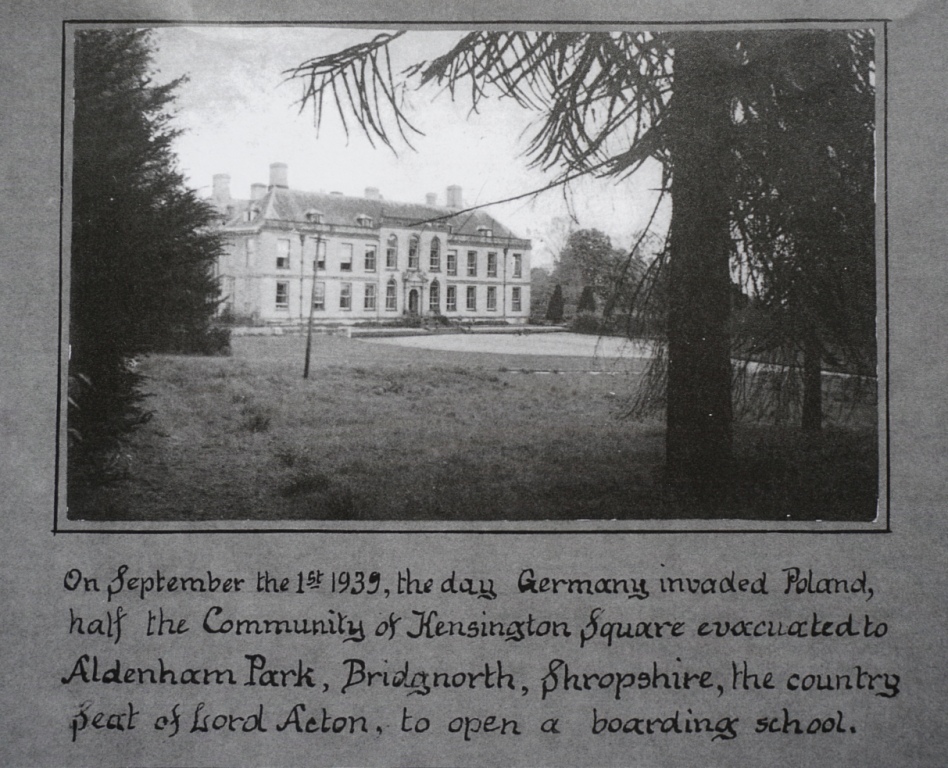

For me it begs the question of how much a sense of place, especially in our childhoods, has an impact on our later lives. I wrote about Waddesdon Manor, home to over a hundred babies and children under five years old. Some of them have memories of their time in the stunning surroundings of Ferdinand de Rothschild’s splendid Loire-chateau inspired country house. Fifty-four girls from the Convent of the Assumption in Kensington spent the war in the house and grounds of Aldenham Park in Shropshire while 400 boys from Malvern College were sent to Blenheim Palace for three terms. Everyone I spoke to or whose memoirs I read made the point that the opulent surroundings, however temporary, that were part of the backdrop of their childhoods made an impact on their subsequent memories. It is a little detail from life on the home front in the Second World War that affected the lives of millions of people.

One final thought: I observed not only how much Brocket Hall meant to the Brocket Babies but also how much the Brocket Babies mean to the people who run the hall today. Their enthusiasm for this part of the hall’s history makes me realise that, as usual, history is at its best and most fascinating when we can see it brought alive, literally in this case, and see or hear the individual stories behind the statistics. Long may the Brocket Baby day continue.