I spent a week in July teaching narrative non-fiction to a group of writers in Devon. It was a memorable week, not least because the weather was perfect and the Arvon Centre at Totleigh Barton is truly a magical spot. My fellow tutor and travel writer, Rory MacLean, enchanted us with his stories from his books and we talked in depth about all aspects of non-fiction. One that really struck a chord with me was what the past can tell you. We all too often think of the past as a black and white world inhabited by ghosts and sad memories but that is only half the story.

COPYRIGHT PHOTOGRAPH BY BRIAN HARRIS © 2006

brianharrisphoto@ntlworld.com

A dozen years ago I worked for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission on their ninetieth birthday commemoration book and I remember distinctly Peter Francis, who was in charge of the project, saying to me: ‘We don’t deal in death, we deal in life and memories.’ It really surprised me but when I thought about it that comment made complete sense. Doctors and nurses, police, firemen and undertakers – they all have to deal with the reality of death but we, who write about the past, work with memories. They are what last when a person moves from this life to the next, or to oblivion, if you prefer.

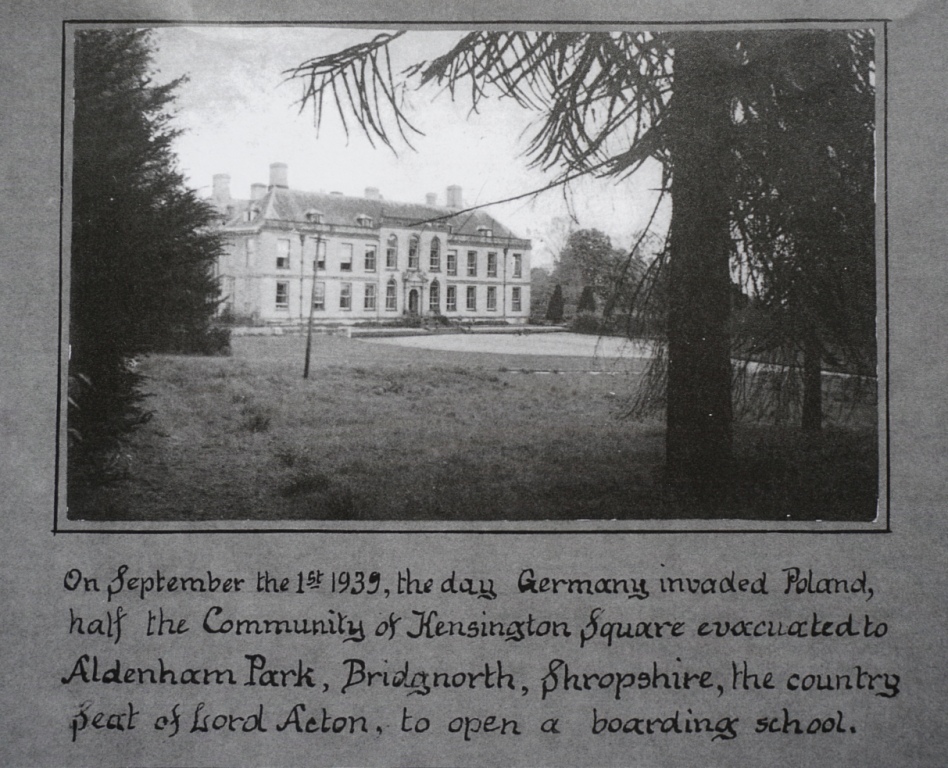

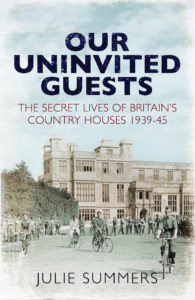

Our job as writers, as I see it, is to nurture memories, to bring alive on the page people who have lived in the past and whose lives touched others in a way that makes it relevant to write about them today. Three from my most recent book immediately spring to mind: Colin Gubbins, Ronald Knox and Gavin Maxwell who, were respectively the head of Special Operations Executive, the Roman Catholic scholar who translated both books of the bible during the war and the author of Ring of Bright Water. Gubbins inspired the special agents who would risk their lives in Nazi occupied Europe, acting with their countries’ resistance organisations and working as saboteurs, assassins, radio operators or couriers. He led with energy but also with empathy and humanity. All who knew him realised what a great man he was. Ronald Knox successfully translated both books of the bible in less than five years, completing a task that many believed would take ten scholars a decade while acting as priest to a girls’ school evacuated to Shropshire. Maxwell, a misfit in so many ways, found his milieu among the agents of SOE who he trained in Northern Scotland in weaponry and survival. The impact of these three men, so different in character but all shaped by the war, touched hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people. But Our Uninvited Guests also tells the stories of people who lived what we might try to call an ordinary life, or at least one that we can more easily identify with: schoolboys and girls, expectant mothers, wounded soldiers, sailors and airmen. Their lives are also important and are to be celebrated. I find the courage and resilience of people fascinating and inspiring, from the twenty-two year old administrator of Howick Hall hospital who drove her Austin 7 through the worst snowstorm of the century to get to work to the seven year old boy who carried messages from Highworth Post Office to Coleshill House on roller skates.

The morning after we all left Totleigh Barton I spent a couple of hours in Exeter Cathedral. It is one of the greatest Gothic cathedrals in Western Europe and it boasts the longest medieval stone vault in the world (96m or 315 feet for those who, like me, love detail). It also has the largest Bishop’s throne I have ever seen. Standing 18m (59 feet) high it is almost impossible to photograph but what is really impressive about it is the fact it is made from local Devon oak held together by wooden pegs and was made between 1312 and 1316. That means the oaks must have been growing about two hundred years earlier. It makes my mind spin when I think that I can touch something, very carefully of course, that is over 1,000 years old.

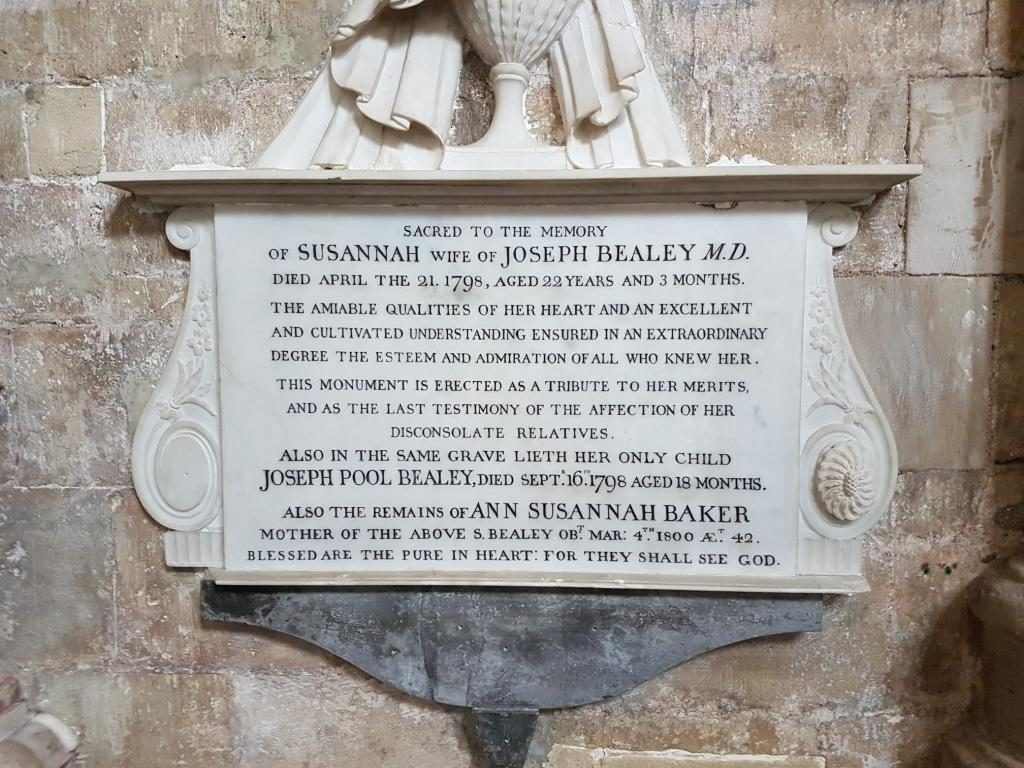

The side-chapels around the choir are full of splendid memorials to knights and their honourable wives. Clutching their swords and resting their feet on dogs with bared teeth, they are destined to spend eternity encased in painted stone, enshrined in Gothic tombs with spiky pinnacles and long Latin inscriptions celebrating their achievements. Or, if you are cynical, their investments. However, I found myself particularly drawn to the memorial inscriptions on the walls of the nave and choir. Simpler than the tombs but equally impressive, they celebrate lives of people who in one way or another were associated with the cathedral. I was delighted to see how many were devoted to women and I was surprised at how personal they were and how heartfelt the lamentations. It is all too easy, as one of the writers at Totleigh Barton reminded me, to think that death was so prevalent in nineteenth century Britain that people became inured to it. Far from it, we both agreed, and this was richly illustrated in the lovely tablets I found in Exeter.

Felicia Jemima, the eldest daughter of William Lord Beauchamp of Powyke, died on 11th October 1813. No age was given but the raw emotion is there for all to see, over two hundred years on: ‘Words cannot express her worth, her virtues and accomplishments, nor the just grief of her lamenting family, but in heaven received by angels, she will meet her due reward’. Rachel Charlotte O’Brien who was burned to death at the age of nineteen in rescuing her infant from a house fire in 1800 is also commemorated. It is heartbreaking to read such detail but also beautiful to think that their memories were so treasured. Susannah Bealey (her stone is illustrated above) was the wife of a local doctor. She died on 21 April 1798 aged 22 years and 3 months. Six months later her only child, Joseph, was buried in the same grave. He was just 18 months old.The ‘disconsolate relatives’ celebrated the ‘amiable qualities of her heart and an excellent and cultivated understanding.’ What a tribute.

Jessie Douglas Montgomery, who died in October 1918, is commemorated as ‘an ardent and unselfish worker in the cause of higher education and for the good of others.’ I looked up details of her life and found that a memorial fund was set up in 1919-20 in her name and that the files for this are at the National Archives in Kew.

Naturally these people commemorated in the Cathedral had standing and their families influence but if you visit any parish church or local graveyard there are headstones and memorials to people who lived long ago but whose lives were colourful and real. I do not think of myself as a maudlin type, just one who loves life – past and present – and who wants to celebrate the extraordinariness of ordinariness.