Welcome to my third newsletter. Last time there was a theme of rocks and snow (and a little bit about rowing) but recently my work has been all about the world wars and their impact on ordinary people.Contents

- Updates

- The Human Cost of War at Fromelles

- The Armed Forces Memorial

- Who to Leave Out

- Pen Thoughts

- Forthcoming Events

Updates

I do not think I can remember a busier spring than 2010 and there is no sign of a slowdown until July. The tasks of lecturing, writing, organising exhibitions, editing and research all clashed during February and March and were fairly exhausting. I have now settled into a slightly more focused, if busy, phase of writing my evacuees book, Relative Strangers, and putting the final touches to the Fromelles exhibition. Meanwhile, The Colonel of Tamarkan (produced by Chrome Audio in 2008), read by Anton Lesser, is being broadcast on BBC Radio 7 from Monday 5th April over eight week days at 3pm under the title The Colonel of the Bridge on the River Kwai. In addition, by way of keeping me fit and sane, rowing has continued through the winter, and the spring has brought with it some glorious early mornings but fast streams.The Human Cost of War at Fromelles men of a Graves Registration Unit in the early

men of a Graves Registration Unit in the early

1920s dig while officers check lists and maps This leather pouch containing a crucifix was one of the personal items found during excavations at Fromelles in 2009

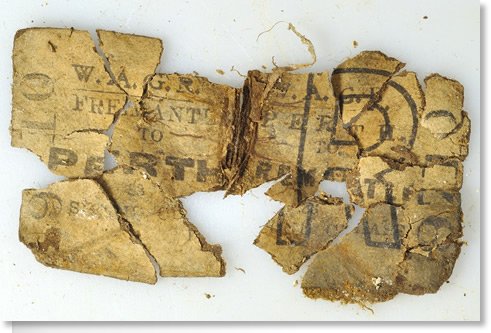

This leather pouch containing a crucifix was one of the personal items found during excavations at Fromelles in 2009 Return ticket from Fremantle to Perth. This really took my breath away, it was so poignant to find something so recognisable and obviously meant to be kept for reuse.At the beginning of March the Joint Identification Board, responsible for pronouncing on the findings of the archaeologists, forensic specialists and DNA experts of the Fromelles project, came up with the names of 75 men who they were able positively to identify. These men died in the Battle of Fromelles on 19th and 20th July 1916 and were buried in a mass grave by the Germans afterwards. Overlooked in the battlefield clearance in the 1920s they were found in 2008 after years of research, and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was asked to oversee the task of exhuming the bodies, identifying them where possible and reburying them in a specially constructed new CWGC cemetery a few hundred yards from the place where they had been lying since 1916. My task has been to produce an exhibition and a book (opening & publication 1st July 2010) to mark the project, since it is the first new CWGC cemetery to be built in half a century. So, with the help of experts who worked on the dig, forensic scientists and the team responsible for the new cemetery, we have put together what I hope will be an interesting overview of an extraordinary undertaking.

Return ticket from Fremantle to Perth. This really took my breath away, it was so poignant to find something so recognisable and obviously meant to be kept for reuse.At the beginning of March the Joint Identification Board, responsible for pronouncing on the findings of the archaeologists, forensic specialists and DNA experts of the Fromelles project, came up with the names of 75 men who they were able positively to identify. These men died in the Battle of Fromelles on 19th and 20th July 1916 and were buried in a mass grave by the Germans afterwards. Overlooked in the battlefield clearance in the 1920s they were found in 2008 after years of research, and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was asked to oversee the task of exhuming the bodies, identifying them where possible and reburying them in a specially constructed new CWGC cemetery a few hundred yards from the place where they had been lying since 1916. My task has been to produce an exhibition and a book (opening & publication 1st July 2010) to mark the project, since it is the first new CWGC cemetery to be built in half a century. So, with the help of experts who worked on the dig, forensic scientists and the team responsible for the new cemetery, we have put together what I hope will be an interesting overview of an extraordinary undertaking.

From my point of view it has been fascinating to compare today’s techniques of exhumation and identification with those used in the 1920s. When the mass clearing of the battlefields took place after the Great War the men who were undertaking the work – and it was deeply unpleasant, let’s not gloss over that fact – had first-hand experience of the war as they were all ex-servicemen. They had unparalleled knowledge of what colour of khaki had been issued at any stage in the war and became detectives par excellence at latching on to the tiniest of clues. In those days it was entirely possible that they would have known personally, or at least known of, a man who was buried in a certain area. Men known to have fallen near to another already identified or to have had a particular feature such as a distinguishing tattoo or to have been especially tall or small, might just have given enough clues to the Graves Concentration Units to identify him. Archaeologists carefully examine the soil in

Archaeologists carefully examine the soil in

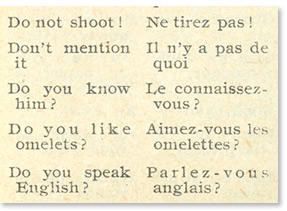

one of the graves at FromellesNow, ninety-three years on, archaeologists by and large had only bones to go on plus whatever scraps of uniform and other objects they could find on the bodies. They had modern techniques such as DNA to help with identification but that was only one part of the puzzle. All the other clues had to stack up, as they did in the 1920s, so a DNA match would be a strong indicator but was not enough on its own. They needed supporting evidence. Since the archaeologists had been told that the Germans had removed anything that might identify a man so that it could be sent back to the family, they were not expecting to find as much as they did – a staggering 6,200 objects. And what amazing little objects they were, too. This is a clean copy of the phrase book that

This is a clean copy of the phrase book that

was handed out to soldiers arriving in France

during the First World War, fragments of which

were found in the mass gravesWhen speaking to the Finds’ specialist from Oxford Archaeology, Kate Brady, I learned that they divided them into six categories: Army issue; items issued in France (a French phrase book, for example); personal items; gifts from the French (a St Benedict medal, small crucifixes of French origin); coins or buttons exchanged with other soldiers and finally, items of trench art such as rings or bracelets. More than anything else these gave an insight into the very human side of this story: men carrying keepsakes, good luck charms, reminders of home-life. All these things point to the firm belief held by the men that they would go home, they would not be the ones to fall. A return train ticket from Fremantle to Perth was particularly poignant, as was the tiny French phrase book with translations for: ‘Do not shoot!’ and ‘Do you like omelettes?’

The saddest thing for me was that their families had been deprived of knowing where their boys were buried. So on a bitterly cold day in the middle of February I went out to Fromelles to attend some of the funeral services at the new CWGC cemetery. Each man was buried individually, as an unknown, but with military honours. Those who have now been identified will receive a named headstone in due course and the families will be able to attend dedication ceremonies if they wish. On that particular day the funerals were conducted in the snow in front of a crowd of two – me and a lady from Ypres. The burial parties were made up of three soldiers from the Australian Army and three soldiers from the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers on either side of the coffin with the British padre burying on one side of the cemetery and the Australian padre on the other. One man at a time. Funeral at Fromelles taken by

Funeral at Fromelles taken by

Revd Cathie Inch-Ogden on 10 February 2010The young soldiers took their responsibilities seriously and one of them said to me during a break: ‘You see, these are our brothers. We all belong to the same family. I’d like to think that it will be my mates who carry my coffin if I die in conflict.’ Quite a sobering thought, as the British soldiers were off to Afghanistan two days after I returned from Fromelles.The Armed Forces Memorial sculptural group on the Armed Forces Memorial by Ian Rank-Broadley

sculptural group on the Armed Forces Memorial by Ian Rank-Broadley

(Photo © John Morris) Left to right:

Left to right:

- Meg Parkes at three years old. We met through research into Far Eastern Prisoners of War and have some great adventures together. Meg is no longer 3.

- Stephanie Hess features in Stranger in the House in the Granddaughter’s Tale. We found we had many interests in common and now keep in regular touch

(Photo © Nicola Barranger) - Amy Clifford, born in 1916, hit her husband over the head with a frying pan when he accused her of being a nag after the war. They were married for over 50 years. She also appeared in Stranger in the House in the Wife’s Tale. I admire her enormously

(Photo © Nicola Barranger)

Which brings me to the Armed Forces Memorial in Staffordshire. But a word of explanation before I continue with that train of thought…

Quite often, after I have given a lecture, people ask me general questions as well as specific ones related to the subject I have spoken about. The two questions I get asked most often are: ‘Do you choose your own subjects? And ‘How do you choose which stories to put into a book?’ To the first question the answer is yes and no. Some books are commissioned – Shackleton, Remembered, Fromelles – and some are ones I have come up with myself: Everest, The Colonel of Tamarkan, Stranger in the House and Relative Strangers. I also get commissions to write articles or, most recently, a handbook to celebrate Our Sporting Life (www.oursportinglife.co.uk), which will culminate in a big London exhibition in 2012. One of the most rewarding smaller commissions was to write an essay about the sculpture on the Armed Forces Memorial at the Arboretum in Staffordshire. I first saw the sculptural groups about six months after they were unveiled. When I saw Ian Rank-Broadley’s sculptures I was taken aback by their immense power. They are truly extraordinary and deeply moving. I really wanted to write a commentary on them somewhere, somehow.

Having spent all my working life in the art world dealing with modern and, therefore, more or less abstract sculpture, it might come as a surprise to learn that I love figurative sculpture, especially the work that appeared at the beginning of the last century in response to the Great War. I felt that Ian Rank-Broadley’s work, eighty years on, captured that same mood of raw emotion as had Charles Sargeant Jagger, Gilbert Ledward and Francis Derwent Wood. So when Ian asked me, more or less out of the blue, to contribute an essay to the book he was publishing on the memorial sculptures I was delighted. I wanted to place his work in the context of the memorial sculptures of the early twentieth century and point out that the nobility and simplicity of the human form is the most effective memorial to the horrors (and stupidity) of war. If anyone has the time to take a detour to the Arboretum it will not be a wasted journey. The book is available on Amazon (ISBN 978-0956051707)Who to Leave Out?

The second question I am frequently asked is about whose stories to include and whose to leave out when I write a book such as Stranger in the House or, currently, Relative Strangers, which is about the evacuee children who came home after the Second World War. As much as anything else it starts with a hunch. When I go to interview somebody I am completely open-minded and expect nothing. The most successful interviews generally begin with the comment: ‘I’m not sure I’ve anything of interest to tell you . . .’ My ears prick up at that instant and I am seldom disappointed. What I am trying to find is the human side of any story. It does not necessarily have to be dramatic or heroic but if it illustrates a human emotion then it can be used in a book to shed light on other people’s experiences. One thing that many people who have read Stranger say to me is that they can see their own stories reflected in those of the women in the book. It may not mirror identically their own narrative but there will be sufficient points of coincidence to make them feel it refers to the kind of experience they had. Very much the same is happening with the book about the evacuee children. It will come as no surprise to you that the gamut of experiences is so rich and varied that it is almost impossible to corral them into one book. And corralling is exactly what it feels like at the moment. So what I have tried to do is to fit the stories I have been told around the historical narrative of the book and I hope there will be some surprises along the way. There are certainly some very amusing stories and those that are writ large in the book generally come from interviewees who have large personalities and lively tales to tell. So a follow-up question I get is: ‘Do you like everyone you interview?’ How hard is that to answer honestly? Of course the answer is no. I would not be human if I liked everyone I came across. But those I am not so keen on are few and far between and that does not mean I leave out their stories. They can be some of the most successful illustrations. The great joy of writing a book like Stranger in the House or Relative Strangers, is that I do get to know some wonderful people who I like to think become friends and that is something truly special.Pen Thoughts

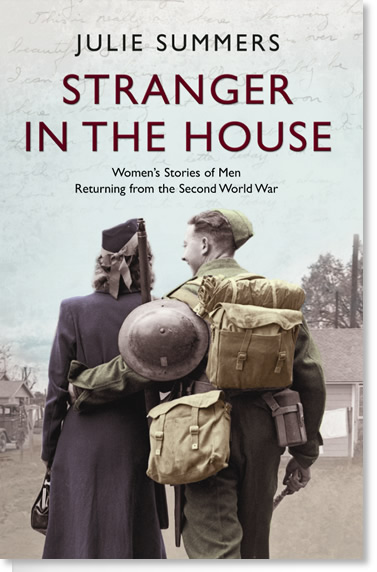

Book covers matter. As do titles. My brother Tim has come up with a cracking title for my next book, which is about the Women’s Institute in the Second World War: Jambusters. Clever? Great fun too and I give him full credit. We had a hilarious hour of bouncing text messages back and forth until he came up with that. But I want to celebrate the art of cover design here, as I imagine few readers really ask themselves who comes up with a book cover or who pulls it together. I have been very lucky indeed with my covers and I have never had one that I was not happy with. I know other writers who are not so fortunate, so I hold my breath every time a new one is suggested. Although I love the cover for Fearless on Everest because it is both evocative and majestic, I think the jacket that Lizzie Gardiner at Simon & Schuster designed for Stranger in the House is the cleverest to date. It is actually a compilation of three images which she worked together into one very powerful and moving photograph that sums up exactly what the book is about. A young soldier has his arm around his ‘girl’ and he is smiling invitingly at her. She is looking straight ahead, calmly holding her shiny handbag, seeming to ignore his advances. They are walking towards what appears to be a village. Their bodies barely touch and his rifle separates his arm from the soft curve of her back. The war – it says to me – has come between them. That image is cropped from a photograph of the couple walking towards a train on a busy station. The background on the cover is a detail taken from a photograph of a cabbage farm in California in 1942 and the handwriting across the top is from a contemporary letter in which it is just possible to decipher the words ‘letter’, ‘today’, beautiful’ and ‘unknown’. All words that feature in Stranger. A really clever composition and beautiful too. And it fits with my interest, which is people and how they are affected by extremes, in this case war.

I will now get back to finishing Relative Strangers and wait to see what S&S suggest for the book cover.

Julie Summers

3 April 2010, Oxford

julie@juilesummers.co.ukForthcoming Events

- Thursday 29 April 12:30 National Army Museum Stranger in the House

www.national-army-museum.ac.uk/whatsOn/lunchtimeLectures - Wednesday 5 May at 8pm Epsom Playhouse Stranger in the House

Epsom, Ewell & District Literary Society

www.epsomplayhouse.co.uk - Thursday 10 June 13:00 The Gateway, Shrewsbury Stranger in the House

www.shrewsburysummer.co.uk - On Saturday 9 and Sunday 10 October the third international Researching FEPOW History conference will be held at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire. Information at http://www.researchingfepowhistory.org.uk/