When I was talking to Australian podcaster, Gabriella Kelly-Davies, recently, she asked me whether I thought truth mattered. ‘Yes, of course truth matters,’ I replied, ‘but …’ and this is where I think we have to define what truth actually means in the context of non-fiction. The truth matters when it is a question of facts that can be checked. You cannot get the date of the start of the First World War wrong nor can you make up the height of the Empire State Building. Those are facts that are checkable. So is the price of an ounce of gold in June 1973 or the date the Thames froze over: January 1940 (for the first time in six decades).

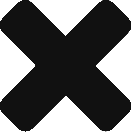

Then Gabriella and I started talking about truth versus fact and here the water gets muddier. One person’s truth can differ from someone else’s to a considerable extent. For example, childhood memories. My sister and I are eighteen months apart, but we very often have different recollections of certain events that happened within our family. I remember being in a road accident when my mother was run into by a man whose car got out of control on the ice on a lane near Burton on the Wirral. It was in the bitterly cold winter of 1963. My sister remembers it too: ‘Afterwards Mum drove us to the Shone’s house and we were given warm milk to help to calm us down. It was either 1964 or 1965.’ Who is right and does it really matter? Truth in this case differs from fact. I know I’m right and she is equally certain her memory is better than mine. And in retrospect I’m sure she is right because in the winter of 1963 she was only 6 months old and would not have had such a clear memory. Does it really matter? It is just part of the muddle of personal memories and were I to write an autobiography, which incidentally I never will, I could serve up my version of personal family events. It’s my memory, after all. Dame Marina Warner, a writer I admire enormously, wrote a book entitled Inventory of a Life Mislaid with the subtitle an unreliable memoir. In using this wording, she signals to the reader that this is her take on the family story, not that of her sister or her parents. It’s a brilliant, enchanting, and at times devastating book and I cannot recommend it highly enough.

As a biographer I do not have the luxury that Marina Warner enjoyed of relying on her own recollections of family life. Facts are what matter to a biographer and if I cannot be certain of something I either have to leave it out or signal to my reader that I am making a best guess as to the missing link between two facts. Lee Gutkind wrote a brilliant book called You Can’t Make This Stuff Up. In it he differentiates clearly between truth and fact. Truth is a personal thing; facts can be checked. When I interview people, especially about their childhoods, I have to be clear when I am quoting them in my writing that this is ‘their truth’. If it differs dramatically from facts that I have checked I make that obvious to the reader while trying not to undermine the interviewees memory. This was particularly tricky when I wrote about the evacuees of the Second World War in When the Children Came Home.

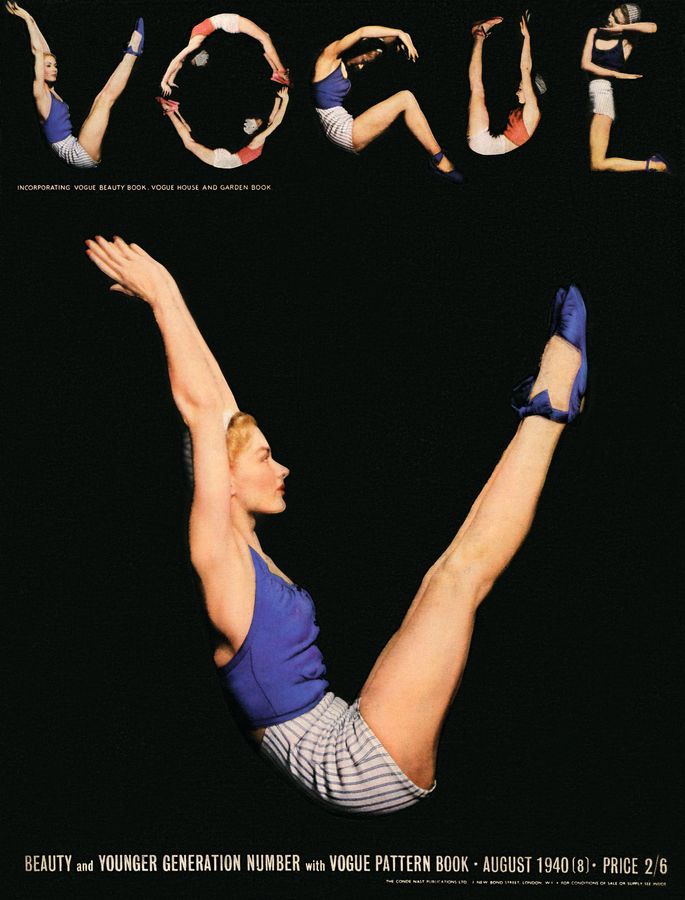

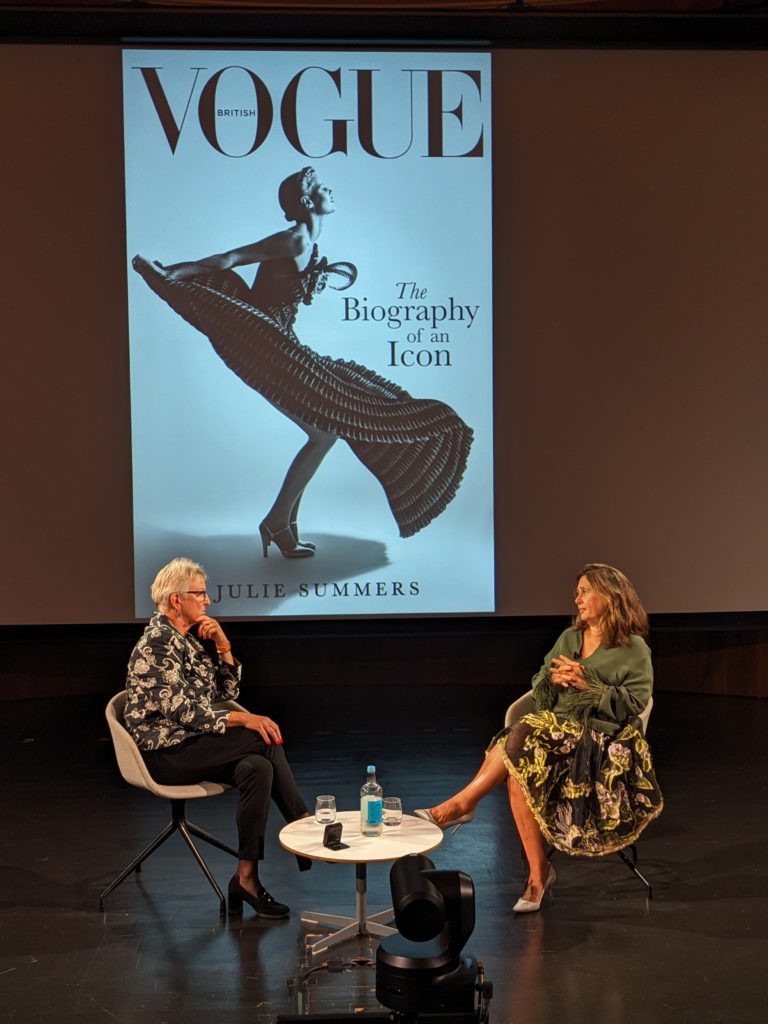

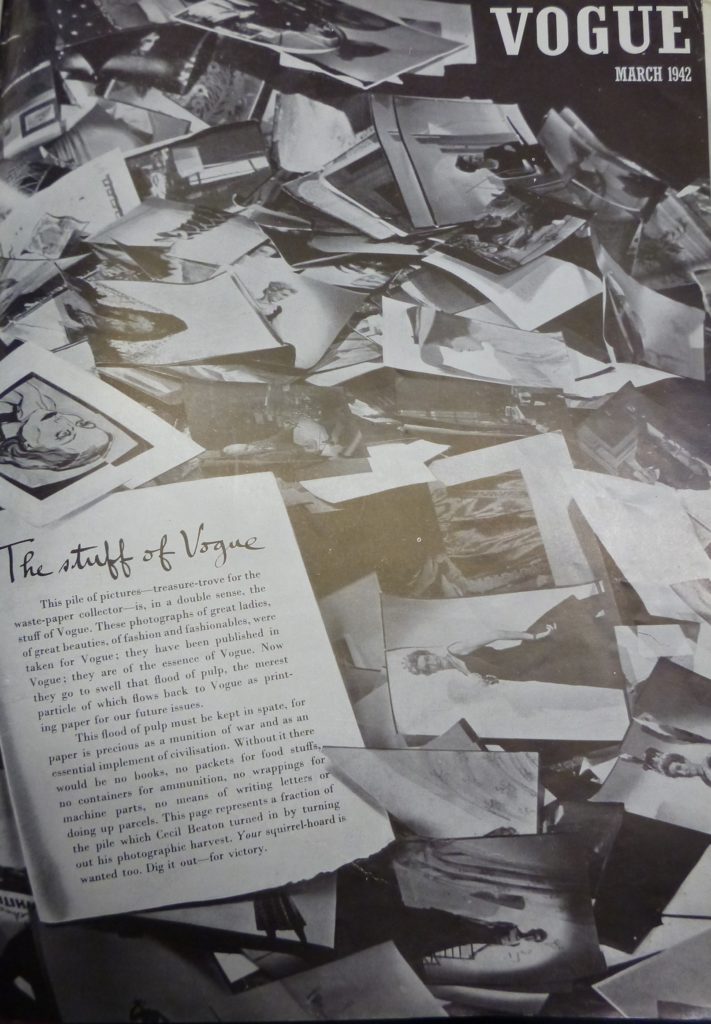

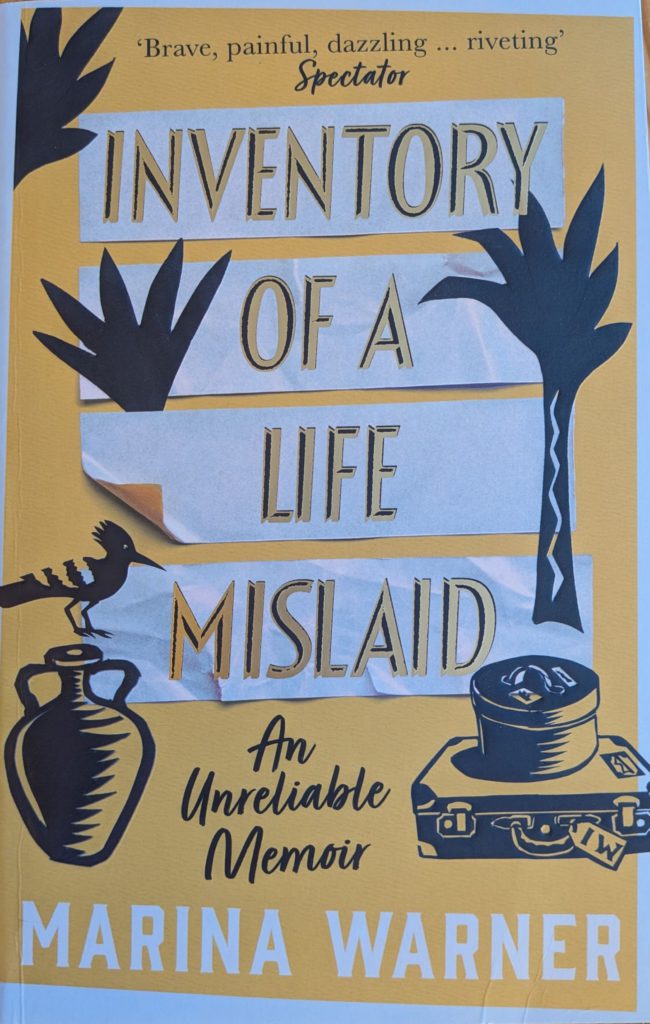

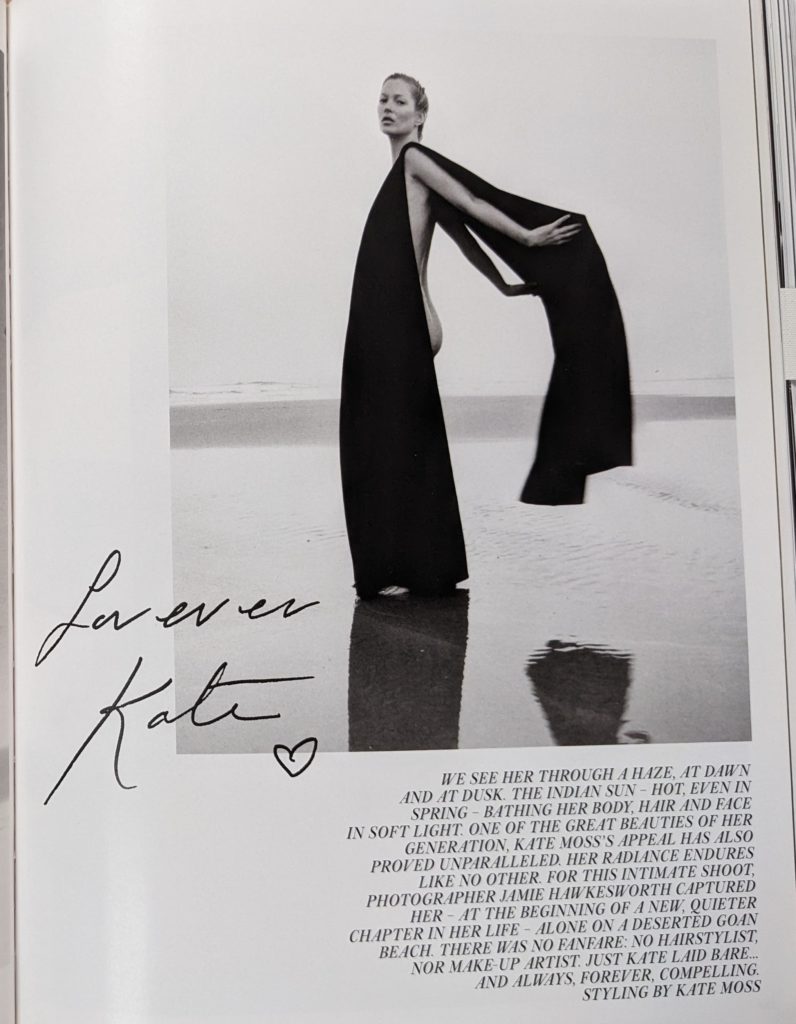

When I came to write my biography of British Vogue, I had to do be diligent about checking facts against people’s memories of their experiences of working for the magazine. Occasionally that got me into hot water. One example involved the model, Kate Moss. She is a woman I admire more than any other Vogue model: a consummate professional and infinitely adaptable. She looks as wonderful in grunge as she does in David Bowie’s outfits for Ziggy Stardust or in a long black cape photographed by Jamie Hawkesworth in 2019. Facts about Kate Moss and Vogue: she first appeared on the front cover of Vogue in March 1993. She was photographed by Corinne Day wearing a pale pink and ice-blue bustier from Chanel Boutique. She has appeared on more front covers of British Vogue than any other model in the magazine’s history: 46 times to date and counting. The only model who comes close is Jean Shrimpton who featured on 23 covers between 1962 and 1974. Where I came unstuck was over her height. In an interview for Vogue by Lesley White in 1994, Kate Moss ‘girl of the year in person’, explained that when her agent initially saw her in Boots campaigns, she concluded her height would rule her out for fashion. How tall is Kate Moss? In the Vogue article Lesley White says 5’5”. Look at her profile today and it says 5’7”. I wrote what I’d read in Vogue but was encouraged to change it upwards by two inches to the widely accepted height of 5’7”. The only way I could possibly have fact checked that was to appear at Ms Moss’s door and ask her politely if I could measure her. Which of course I did not.

How many editors has Vogue had in the past 109 years? Was Edward Enninful the first male, gay, black editor? This became a fascinating game of hunt the facts. To answer the second question: no, no and yes. Edward Enninful was definitely the first black editor of British Vogue. The first gay editor was Dorothy Todd and the first male editor, albeit only for six months, was Harry Yoxall. But it is true that Enninful was the first with all three attributes combined. The answer to the first question is even more intriguing to my mind, but then I am variously described as a pedant, a nerd or a ferret. In the time period of my book: 1916 to 2024 there were 12 editors who held the office for between 18 months and 25 years. They include Audrey Withers, Beatrix Miller and Alexandra Shulman, who between them accounted for 67 years. If you want to know who they are I have listed them at the bottom of this blog.

Please note that Elspeth Champcommunal, a name very familiar to the fashion industry, does not appear in the list of Vogue editors. That is because she never was the editor. She was the fashion editor. The editor herself at that time was a woman called Ruth Anderson. How can I be so sure? Because in 1937 the writer Lesley Blanche was commissioned to write a survey of the first 21 years of British Vogue and she mentioned Miss Anderson as the editor between Dorothy Todd’s two periods at the magazine. If I’m losing you, please bear with me, as it has an impact on another very famous woman in Vogue’s history: Anna Wintour. When it came to writing the story of the magazine for the golden jubilee edition in 1976, it was simply more glamorous to have the exciting fashion designer, Elspeth Champcommunal, as the second editor of Vogue than the less well-known Ruth Anderson. How did this rewriting of Vogue’s history occur? Miss Anderson had no advocate and Miss Champcommunal’s daughter claimed her mother had held the role. It became the accepted story.

And now to Dame Anna Wintour. A name so respected and feared by many in the fashion and publishing industry that I will surely be warned against publishing this blog. But here goes. In June 2025 the BBC reported, amongst many other news outlets, that Anna Wintour was stepping back as editor-in-chief of American Vogue after 37 years. So far so good. ‘a role she has held longer than any other editor.’ Oops. No. That palm goes to Edna Woolman Chase, the editor appointed by Condé Nast himself, who held the role for 38 years from 1914 to 1952. OK, I’m nitpicking here but it’s my job to pick nits. Incidentally, Mrs Chase worked for Vogue for 60 years which I believe is another record in its own right. The Guardian claimed Wintour had begun as editor of British Vogue in 1985. Not so. She started at Vogue House in April 1986 and her first issue was July. Another source claimed she edited the British edition for three years. Again, no. Her editions run until November 1987 and number seventeen. Her successor, Elizabeth Tilberis, took over the reins in the late summer and published her first issue in December 1987 with Naomi Campbell on the front cover.

Does any of this really matter? After all, Anna Wintour is the most famous name in Vogue’s history and surely her reputation is more important than my research. As a biographer I think it does. I have an obligation towards my reader to be as accurate as possible. It is a contract between me and that individual and one I will do my utmost not to break. They have been kind enough to buy my book in the first place and give up hours of their lives to read it. If I break that contract by making guesses and assumptions, I will lose their faith. So while I won’t be knocking on Kate Moss’s door with my tape measure, I will continue as I research my next book, to dig as deep as I possibly can to uncover accurate facts and bring them to light even if they sometimes conflict with received wisdom. I believe that truth matters.

Link to the podcast https://www.biographersinconversation.com/s03e19-julie-summers-british-vogue/

Vogue Editors 1916-2024

Dorothy Todd 1916-1919

Ruth Anderson 1919 to 1923

Dorothy Todd February 1923 to September 1926

Michel de Brunhoff/Harry Yoxall September 1926 to March 1927

Edna Woolman Chase March & April 1927

Mrs Meynell May to July 1927

Alison Settle July 1927 to October 1935

Elizabeth Penrose 1935 to September 1940

Audrey Withers September 1940 to December 1959

Ailsa Garland January 1960 to April 1964

Beatrix Miller June 1964 to June 1986

Anna Wintour July 1986 to November 1987

Elizabeth Tilberis December 1987 to March 1992

Alexandra Shulman April 1992 to June 2017

Emily Sheffield (acting Editor-in-Chief) October 2017 issue

Sarah Harris (acting Editor-in-Chief) November 2017 issue

Edward Enninful September 2017 to January 2024 (final issue March 2024)